At an age when most people are looking back ruefully on how much quicker they used to be, Clair Bossum was galloping toward becoming the fastest, and possibly most accurate, scroll saw virtuoso in the West. At 71 years old and twice widowed, Clair had already retired from a lifetime career only to plunge headlong into another. This time around, he has become one of the most prolific practitioners of the slender blade, taking small pieces of wood and turning them into elaborate and dazzling works of art. His twin canvases are fretwork and intarsia.

“Intarsia,” Clair explained, “is a type of inlay work in which solid wood is cut into shapes and assembled like a three-dimensional bas relief puzzle. The library definition of fretwork is ‘decorative perforated wood or metal.’ Both are done on the scroll saw, so to me, they seem like a natural pair.

“Fretwork and intarsia are all about cutting wood accurately,” Clair continued, “and that challenge is what makes it interesting. When doing fretwork, every piece has to be both accurate and square or the myriad of pieces will not fit together properly. With intarsia, the game is to make sure that the adjacent pieces are so close and the interface lines so tight that you can not even slip a piece of paper between any of the adjacent parts.” Considering the complexity of his work and the vast number of mating surfaces involved, that statement is even more amazing than it seems.

An artist even as a young child growing up in Hazel Park, Michigan, Clair chose for his initial career something that would hone his natural inclination toward accuracy. “After high school, I started working for a company making precision metal cutting tools, and ended up doing that for my entire career at a number of companies. There were some interruptions. First, there was a four-year stint in the Army from 1955 to 1959, where I was stationed much of the time in Germany. After that, it was back to work for two years before returning to the Army. This time I went to Korea, and stayed in the service until 1965. After leaving the military, I worked for Chrysler in Detroit until 1980.”

About that time, Chrysler started laying people off. Boeing, the huge Puget Sound based aircraft manufacturer, showed up on a hiring expedition, and Clair had a new employer. That prompted a move to the Pacific Northwest.

“In 1980, I was living in Puyallup [Washington] and searching around for a hobby. While trying to decide between stained glass and wood, serendipity intervened. A coworker asked me to make a rocking horse. I did, and for the next two years I made rocking horses and sold them to coworkers, picking up tools as I needed them. I used to make 25 at a time, and have made at least a few hundred over the years.

“After two years, I was laid off and moved to California to work for Rocketdyne. During that time, I did oil painting, because my apartment was too small for a wood shop. Three years later in 1986, Boeing called me back. I returned to the Pacific Northwest, this time to Auburn [Washington], and I stayed with Boeing until my retirement in 1998.

“After the move to Auburn, I picked up where I had left off, making rocking horses, but in 1996, I shifted gears. With retirement staring at me just two years away, I decided to look for a hobby that required less space and used smaller pieces of wood. Instead of one hobby, I found two, and started making both intarsia and scrollwork.

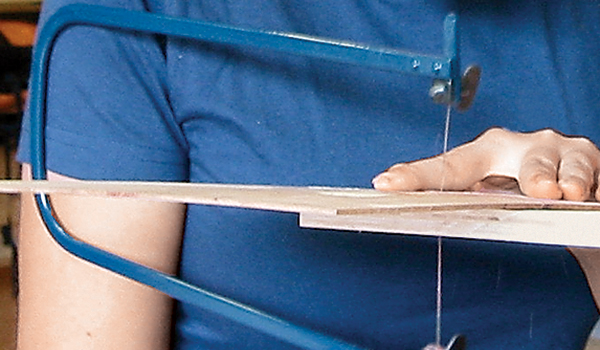

“When I first started, I used a band saw for cutting out the intarsia pieces. That was how I was taught, and was the conventional wisdom at the time, but I soon changed to a scroll saw, which works much better. My cutting tends to be very fast and accurate, probably because I spent my working life doing precision setup and grinding.” Still, he was not satisfied, and as a man who had made tools all his life, there was a natural inclination to improve on what he had.

“Over the years, I have completely modified my scroll saw to make it easier to do my work. I put quick-release cams on to allow me to change blades in just five seconds, and added a much larger four foot by two foot floating work table. Though the table surrounds the blade, it does not actually touch the machine. As a result, it is unaffected by the vibration of the saw. That vibration-free table coupled with the quick change blade cams improved my cutting accuracy and speed immeasurably. I suspect that I now have the fastest scroll saw that exists.

“After I retired, I decided I wanted to win a ribbon for something I did, so I entered a lighthouse into the Puyallup Fair. It won first place and best of show ribbons. Before the year ended, I had another dozen from a variety of shows and venues. Over the past two years, I have collected some 36 first place ribbons.”

Don’t think this is his only hobby, though, or even his only source of blue ribbons. Along with woodworking, Clair raises irises, and currently has some 19 different species growing on his property. As he does with wood, he competes at local flower shows. “I’m the first person in King County to win shows two years in a row,” he told me proudly. “Two years ago, my flowers took all six positions on the judges’ table during the final round for the coveted title ‘Queen of the Show.’ That made it a foregone conclusion that one of mine would win.”

Not content to reap honors, Clair decided he wanted to do more for others. “Recently, I started thinking about teaching. I did a presentation for the NW Carvers Association, and soon found myself teaching at the Rockler [Woodworking and Hardware] stores here in the area as well as at local woodworking guilds. I also teach people one-on-one here in my shop whenever they ask, but I don’t ever charge anyone money for that.

“This year, I started doing volunteer teaching for the woodworking program at Wilson High School in Tacoma. There, a former carpenter named Marilyn Obiatte has spent the last year trying to resurrect a woodshop that had fallen into disuse. Hired this year, Marilyn says the shop was so cluttered that you could not even walk through it. She invited me to come in and talk to the kids, and it has morphed into a regular activity.

“I’d like to do more with teaching,” he told me, pointing out that “it has been a two-way learning experience. The kids themselves taught me how to teach them. Initially, I was trying to tell them how to do what I do, but that did not work well for them. Then I tried something different. I simply did a project in front of them. The difference was amazing. They immediately picked it up and ran with it.”

Clair sums up his philosophy about woodworking and teaching with words that sound a lot more like Dr. Seuss than Plato. “I love what I do and I do what I love,” Clair intoned. “I have a passion for this that I simply can’t overcome.”

I’ll bet the ranks of collectors who own his pieces and the cadre of kids and adults who benefit from his generous tutelage are quite glad that he can’t overcome his passion, and fervently hope he never does.