Back in the days when Chris Krauskopf was working for the biotech industry in Seattle, he used the woodworking skills he had picked up from his father and grandfather to make furniture for his home. One day, he invited one of the doctors he’d been working with over to his place for dinner.

“When he saw the furniture I’d been making, he asked, ‘Where’d you get that?’ When I told him I made it, his jaw dropped, and he asked ‘What are you doing in the biotech industry?'”

Chris did not immediately quit biotech and go into the woodworking business for himself — but when the company he worked for was purchased by another company, which liquidated the whole staff, it provided an option.

Chris moved to Kentucky, where he makes furniture on commission — all done with hand tools. “Before I moved to Louisville, I had a router and a jigsaw, a couple of other things. When I moved here, I decided I didn’t want to go that route,” Chris said. “I liked the quiet; I could be efficient: I sold the power tools to buy more hand tools.” It’s also, he pointed out, “a little hard to saw off all your fingers if you’re using a hand saw: you stop after the first nick.”

Chris likes the distinctive look and character of the pieces he makes, noting that, often, “furniture I’ve made has the look of antique furniture — which makes sense because it’s made using the same tools, in the same finishes.”

Those tools include a variety of hand planes; a high-tension, handheld frame saw he made for rip cutting and thickness cutting, and more. Most of his tools, Chris acquired at flea markets and antique malls; he will occasionally visit an antique mall or the Midwest Tool Collectors Association for supplies like blades for his planes.

He does have a thickness planer that he uses on occasion (“Sometimes, people give me lumber of crazy dimension,” he said.) “If I need to work with sheet goods, I buy it as sheet goods.”

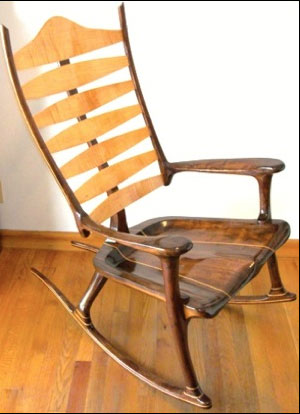

“Kentucky has the greatest cherry and walnut in the country,” Chris said, “and sometimes excellent figure in maple.” Along with mahogany, “those four woods are my most common” to work with, he said. He makes an effort to select a piece of wood that will best match a client’s taste and best highlight the piece he’s working on, noting that “the most figured is not always the best. You don’t want to come in the door and have a chair that’s very, very ‘loud.'”

Sometimes, a customer’s choices also impact a project. Chris recalled one commission, acquired through a neighbor, from an elderly German woman who wanted a sewing table for a particular spot in her small home. “I made up a drawing and took it to her, and she said, ‘Ja, ja, das ist gud,’ so I made it up out of poplar — she wanted poplar. About a week later, she and her daughter came to my house with a can of lantern green paint, ‘OK, now paint it!'” When he delivered the piece the following week, the woman, her daughter, and a friend stood up and clapped. “They gave me a standing ovation; I guess she’d been trying to find something for that spot for who knows how many years.”

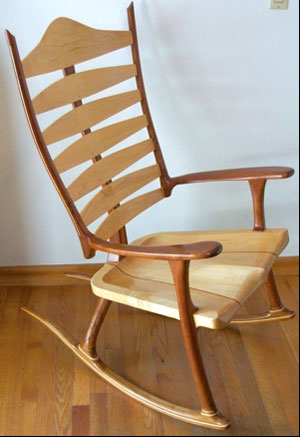

The pinnacle of Chris’s woodworking, however, is his rocking chairs. While he does few chairs compared to his other projects, “I use my rocking chairs as my showpiece,” he said. “They create an impression of quality and ability. At shows, people go, ‘Those are beautiful. If you can make that, you can make “this” for me.'”

Chris spent about three years coming up with his current rocking chair design, which is about a year old. He went through six prototypes, which he brought in to his woodworking club and had members try out. “They let me know; they’re not very shy,” he said. By the time he brought in the last chair, “Everybody who sat in it was smiling.”

The chairs, which take between 170 and 180 hours apiece to make, are built for specific individuals after Chris takes measurements of their bodies. The chair itself, too, is modeled after the human body, with a single spine up the back, along with “ribs.” “I think it’s the most comfortable wooden rocking chair you’re ever going to sit in,” Chris said.