Chris Connor has always been an avid bicyclist. At one point, he said, “I thought, ‘Maybe I should build a plywood bicycle for my wife.'” What grew from that thought — and his previous experiences — is Connor Wood Bicycles.

Chris had tinkered in the shop as a kid, with a grandfather who encouraged him and set him up with a workbench. In college, he studied art, eventually graduated with a degree in political science, and went into jobs in banking and high-tech marketing. “All the while, I still had the desire to create things of beauty with my own hands,” Chris said.

His brother, Steve Connor, seems to have had the same sort of desire, since Steve ended up becoming a maker of classical guitars. As Steve’s guitar business took off, Chris spent some time helping him in the shop. “It was pushing me to be a better woodworker, to build more and more difficult things,” he said.

As his brother reached a point when his business was growing, Chris left his job in high-tech marketing in Boulder, Colorado, and moved to Massachusetts to help out in the guitar business. “I was able to bring my modest furniture making skills,” he said, plus, “I’m sort of a jig master.” He designed jigs to make various aspects of the guitar construction repeatable, focusing on things like creating specific angles or specific geometry.

On weekends, when the Connor brothers weren’t building guitars for the business, they would work on boats, which shared a composite construction with guitars.

Eventually, however, Chris determined that, “My family couldn’t make staying on the East Coast work, and we headed back to Colorado.” However, “I’d gotten that bug of what it’s like to work for yourself and build a thing of beauty.”

Guitars, however, were just not his thing. “I don’t even play guitar, and my brother does that so beautifully,” he said. Chris made furniture for a couple of years, but continued looking for something that offered more interaction, and was, essentially, functional art.

Then, he had the thought about building a plywood bicycle for his wife. And realized that, like guitars, bicycle construction requires a lot of specific angles, with another similarity being that both had beautiful, flowing lines. “It was sort of like a Venn diagram, where all the circles crossed in the middle. Eureka: building wooden bicycles!”

After receiving that inspiration, Chris did some research, sure that wooden bicycle making was such a great idea that it would be a crowded marketplace. He found that was not the case.

What did work for him was that so many of his skills, and even the jigs and fixtures he’d created, from guitar building came in handy when making wooden bikes. With a guitar, he said, you’d need to find the proper neck angle. With a bike, it’s the right angle for the chain stays and seat stays. The various sleds he used for cutting mortises and to get the correct neck joint on a guitar translated into “a ton of little sled fixtures” for cutting parts while holding things precisely and repeatedly on a bicycle being built.

The steam bending he’d done for guitars means he’s comfortable steam bending curved components of his bikes, like handlebars. And even the previous years’ weekend boat building expeditions came in handy, since the marine adhesives “translated right into bicycles,” which also need to withstand the elements.

Chris works out of what he describes as a standard woodshop, with a table saw and band saw as the shop’s workhorses. (He uses a Rikon band saw, and was recently asked to construct a corporate logo wooden bike for that company.) Just as with the guitars and boats, he does a lot of composite laminations, cutting multiple strips of wood and then flip-flopping them to avoid continuous grain lines.

A Performax 22″ wide drum sander is “wonderful for creating precision, gluable surfaces.” Plus, the shop contains “a huge collection of routers. One of the keys to efficiency is having lots of routers,” Chris said. While he does sometimes change the setup on his router table for different procedures, for the most part, he has handheld routers specifically dialed in to one application apiece. “That’s the router for this cut,” and another might be the router for “that cut,” he said.

“Steam bending and Kevlar® differentiate my bikes,” Chris said. After steam bending certain parts, like handlebars, seat stays or chain stays, he puts layers of Kevlar, the material used in items like body armor, into the laminations. The Kevlar, Chris said, has incredible strength — but remains flexible.

“The Kevlar’s flexibility lets wood behave as wood,” he said. “The two main reasons to have a wooden bike are, 1) it’s a look unlike anything else, that’s visually stunning; and, 2) from a practical standpoint, it’s not for the light weight, it’s not for strength, but where wood does shine is it inherently absorbs vibrations from little bumps and doesn’t telegraph them to you body. It creates an incredible, smooth ride that’s a delight for a rider to experience.”

For all of Chris’s bikes, the primary structural wood is ash, with black walnut used occasionally as an accent. “Ash has a great mix of the properties I wanted,” he explained. Having been used as a tool wood for thousands of years (it’s referenced in The Iliad), and today in Louisville Slugger® baseball bats, ash, Chris knew, was impact-resistant, strong, and could be modified with steam bending. “I never wanted to question the base integrity of the wood,” he said. “It has to behave like a bike. You have to be able to ride it without worrying about it coming apart.”

Ash was also a sustainable American hardwood that Chris could get locally and had bold grains and an inherent beauty. “It’s not to be confused with something else,” Chris said. “There’s no question that this is not just a paint job; this is a real wooden bike.”

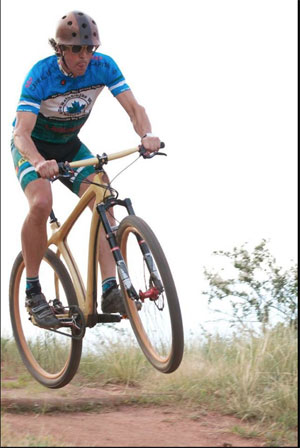

Most of the bikes he has made are hot rod cruisers or “scorchers” city bikes, but he recently began building mountain bikes as well. Constructed of ash from a tree that had been hit by a car in Chris’s town of Denver, his first mountain bike model was entered in the Leadville 100 mountain bike race out of Leadville, Colorado. “It was meant to demonstrate that these things aren’t toys,” Chris said. “The bike rode wonderfully for the entire race, with no damage, over a hundred miles in the toughest conditions.”

As another, ongoing test, Chris is still riding his original prototype bike, a cruiser with “the least sophisticated design and construction.” His intent is to ride it to “see what it does with time, and different conditions.” Since most wooden bikes haven’t been around for decades, he points out, there really isn’t data on how they hold up over time.

Chris points out that he is not trying to replace titanium as a material for bike construction. In the bicycle application, “Wood is not superior to other mediums,” he said. “Nobody is seeing this on the podium. First and foremost, these things are functional art: it’s unique, it’s beautiful, and it’s fun.”