When Washington-based woodworker Willie Sandry gets excited about a project, he jumps in with both feet. And considering he’s a physical therapist, he can take these leaps forward without hurting his back.

“My biggest reward of PT is inspiring someone to turn a sedentary life into one filled with fun, useful activities.”

As a young man, Sandry would help his father, a contractor, build decks and refinish floors during summer breaks from school. Two uncles — one a boat builder and the other a woodcarve — also were early woodworking influences.

Sandry’s mother, a writer, helped shape his publishing pursuits, too. “In the most basic sense, I build things and write about them,” Sandry says. “Talk about the acorn not falling far from the tree!”

Over the years, Sandry has gravitated toward Arts & Crafts style furniture, and we’ve published several of his projects embracing this aesthetic. He’s developed a particular fondness for Charles Limbert.

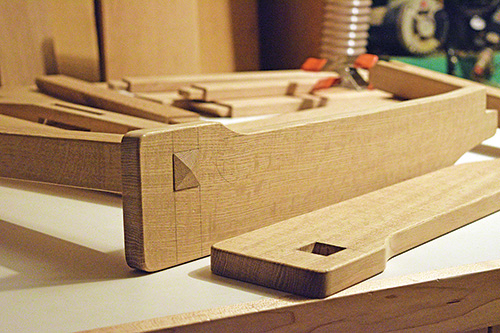

“Sometimes I’ll do Limbert reproductions, trying to match every angle and dimension. Other times I’ll let functionality guide the design and add in cutouts and inlays reminiscent of a Limbert piece,” Sandry says. “Limbert used angles, curves and cutouts in a recipe that almost always produced a beautiful piece.”

Among his résumé of projects, Sandry says the one he’s just completed is often his favorite. But a special example that stands out is a master bedroom suite that includes a bed frame, dressers and nightstands. He’s also pleased with his Limbert Hutch.

Sandry’s work demonstrates a high degree of skill. But of course, no one becomes a talented woodworker overnight. Sandry admits that it’s taken many years to gain proficiency with the craft. He feels the evolution of his skills started with the ability to make joints fit together well. Then, he focused on his project design skills, and last came the ability to apply a sprayed finish well.

Adding More Skills

A number of years ago, the high cost of buying kiln-dried, quartersawn white oak lumber prompted Sandry to build a lumber drying kiln. Aside from cost savings, the kiln also helps him better control his lumber’s quality.

“It changes the whole way I look at my lumber supply,” Sandry says. “I don’t calculate down to the board foot anymore. I buy by the stack and not by the board.”

Arts & Crafts has even inspired Sandry to try his hand at leatherwork. When he wanted to sew leather cushions for a Morris chair and ottoman years ago, he took a class to learn how.

One aspect of the woodworking process Sandry has decided against is sawing boards directly from the log.

“I debated about buying a band saw mill one year, but that same year a log rolled onto a sawyer friend of mine. He broke his pelvis, and it forced him to retire early,” Sandry recalls. “Right then and there my wife made me promise I wouldn’t get a lumber mill.”

But provided he stays away from bucking logs, Sandry says his wife “heartily” embraces and encourages his woodworking. It’s also sparked interest from his twin teenage sons who occasionally build with him.

Sandry’s woodworking is an avocation that continues to offer new opportunities for both learning and enjoyment. “If a chair needs a leather cushion, let’s sew one. If a cabinet needs a leaded glass panel, get out the soldering iron and let’s do this thing. And if someone reads about my work and is inspired to make something like it, well that’s just the cherry on top of it all, my friend.”