The entertainment center is a relatively new addition to the lexicon of American furniture forms, one that was necessarily developed long after the era of the Arts and Crafts movement. Nevertheless, it’s possible to design an entertainment center reflecting this traditional style by bringing to the piece some of the identifying characteristics common to the Arts and Crafts movement, a style that dominated quality American furniture making at the dawn of the 20th century.

This entertainment center (which I built for my son Andrew) was designed to provide support for a large video gaming monitor as well as the game systems and storage for the game cases. Fortunately, those game cases are the same size as DVDs, so it will store them equally well. To that end, I borrowed and compiled design elements from classic Arts and Crafts examples: rectilinear details, tapering front rails and the repetitive lines of the exposed storage area are a few examples.

Constructing the Front

The case is constructed of three subassemblies: the plinth, which lifts the piece from the floor; a solid-oak front (a modified face frame), which creates the shape of the entertainment center’s silhouette; and a central box that holds the center’s various storage compartments.

I built the front from solid oak, tenoning the various stiles into the bottom front rail, while the top rail sits behind the stiles and is screwed to their back faces. In my original drawings of the entertainment center, the top rail was mortised to receive tenons on the stiles, but — at least to my eye — the presence of that top rail created a visual dead space over the storage slots.

In a bit of an unusual technique, I glued and screwed the back of the bottom rail to a cleat that would catch the lip of a rabbet on the plinth deck.

The most complicated feature of the entertainment center’s construction was the installation of the tapered stiles. In order to open up the spaces above the banks of storage slots, I decided to stop the top rail at the stile on either side of the central compartment.

This would have left those tapered stiles unsupported (with no rail connected to them) at the top prior to the installation of the unit’s top. In order to stabilize the tapered rails, I temporarily ran the top rail long, across the top of the storage slot openings, attaching it to the tapered stiles with screws. Later, I cut the ends free after the front was screwed in place. (Note: these rails are tapered only after they have had the tenons formed on one end and test fitted in the front.)

Making the Plinth

My dad was a cabinetmaker for much of his working life, building custom cabinets for dozens of kitchens and bathrooms, as well as dozens of commercial offices in northern Ohio. The plinth — or base — for each of his cabinets was constructed of 1 x 3 material nailed together into a ladder-like frame to which the cabinet front was attached and on which the cabinet was constructed. This is the approach I used for building the plinth of this entertainment center.

I built a ladder from spruce furring strips ripped to a 2-1/8″ width that I fastened together with 1-5/8″ drywall screws. The ladder was built without a front rail in order to create visual space under the arc at the bottom of the cabinet front.

I then attached two glue blocks on the inside front end of the ladder’s long end pieces. These provided me with my initial attachment points for joining the plinth to the front. This attachment was reinforced as other components of the case were installed, by attaching them to the front and to the plinth.

Assembling the Case

The case of this entertainment center is fabricated from oak plywood. Plywood is much better for the case than glued-up panels of solid oak for several reasons. First, plywood panels need only to be cut to size. It isn’t necessary to glue up narrower boards and then surface them before sizing them. Second, plywood is dimensionally stable. It doesn’t shrink across the grain, which eliminates the need for frame-and-panel construction. Plywood is also much less expensive than enough solid wood to create the top and end panels. And finally, plywood is much lighter, and speaking from the point of view of someone who carried one end of this cabinet into my son’s second floor apartment, a heavier cabinet would not have been wise.

The plinth deck is a sheet of paint-grade plywood which is rabbeted on its front bottom edge so it could be screwed to the oak cleat on the front’s bottom rail. I then screwed the bottom to the plinth with 1-5/8″ drywall screws, giving me a solid base for the rest of the construction.

Next, I removed the screws attaching the front’s top rail to the tapering outside stile and cut that rail off on the outside of the stiles, planing the end grain flush with their outside edges. The end panels are made from oak veneered plywood, but to economize on the oak plywood, I created the interior walls from two pieces of plywood (the front and rear dividers). The front section was oak plywood, but the back section was paint grade ply. The end panels and the front dividers require careful preparation: 1/4″ x 1/4″ dadoes need to be milled onto these surfaces to accept the ends of the short oak shelves that will be housed there (see the Drawings). The dadoes on the end panel must be long enough (15″) to allow the shelves to be slid in from the back of the cabinet prior to the installation of the rear dividers. The front edge of these dadoes are blocked by the cabinet front.

After I finished those dadoes, I plowed the slots for the game case shelves. It was now time to install the two end panels. To stabilize them until the top had been installed, I first temporarily placed corner brackets into position, screwing these brackets to the base of the cabinets and the inside face of the end panels. I typically use these brackets to ensure that case pieces remain square while the glue is drying, but I’ve found them useful in many other assembly contexts as well.

I screwed the bottom of each end panel to the plinth, and at the same time I applied glue to the forward edge of the end panels and clamped them to the front until the glue had cured. Following that, I installed cleats (see the Drawings for details) on the top inside face of each end panel. These cleats are the primary means of attaching the top. From oak plywood I cut out the top and secured it to the cleats, then I removed the corner brackets.

Once the top was attached, I put the cabinet face down and installed cleats on the top and the plinth deck to which I would screw the front and rear dividers. First I had to notch the front dividers to accommodate the top rail. Then I secured the front divider to the cleats with glue and screws. Now is the time that you need to put the solid oak shelves into the 1/4″ x 1/4″ dadoes that you cut earlier. As I was preparing to mount the small shelves that would contain the game boxes, I realized that a narrow band of the paint-grade plywood I used for the bottom of the cabinet would be visible below the bottom shelf, so I removed the top veneer layer of the paint-grade plywood from that visible section and replaced it with a strip of oak veneer. Sometimes late “discoveries” like this happen even to very experienced woodworkers.

After that repair, I glued the shelves into their grooves, fitting each with a few strokes of a block plane. As I did so, I glued the shelf stops on each shelf with a quick rub joint. (Note: As you can see in the photo at right, the rear divider isn’t installed until after all the small shelves are in place.) Four additional cleats hold the two large shelves — mount them as shown in the drawings. Then attach the shelves to the cleats … I made mine from oak plywood with a solid oak facing on the front edge.

Building the Doors

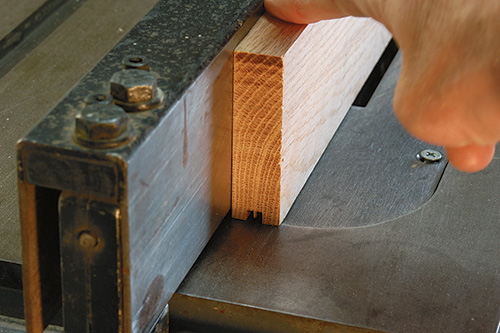

The doors are made from solid oak using frame-and-panel construction. I first chopped the mortises in the stiles and cut matching tenons on the rails, fitting each to its mortise with a shoulder plane. (See the Drawings for details.) Then, on the table saw, I plowed the 5/16″ x 5/16″ grooves in the rail and stile stock that would receive the edges of the door panels, after which I turned my attention to the raised panels that would be fit inside the frames.

The flat front face of each door panel is decorated with walnut stringing made with a quick-and-dirty inlay technique. I first used a hollow-ground planer blade on my table saw to cut clean grooves on the face of each panel. I left that same blade in the saw to rip off thin strips from a walnut panel I had thicknessed to the exact width of the grooves. After applying a little glue to the grooves, I tapped the strips into place. I completed the process by planing each strip flush with the surface.

Since the door panels show their flat faces in front, I raised the back surface of each panel by planing wide bevels all around to reduce the edge thickness. The bevels were laid out by marking one line on the edges of each panel about 5/16″ from the front surface and a second on the back surface of each panel about 1-1/2″ from the edge.

After dry-assembling each door to check the joinery, I glued the mortises and tenons and clamped the assembled door, leaving it to cure on a flat surface.

My setup for mortising door hinges employs a vise, a catch block and one of the corner brackets I used earlier when installing the end panels. This presents the door at a convenient height for handwork and keeps it stable under the force of chisels and a mallet.

The mortises on the door frame, however, have to be chopped on the assembled cabinet in less convenient circumstances. However, despite my gauge and my careful installation, I still managed to goof in the installation of one door. I could have filled the hinge screw holes and re-installed the hinges. (Like I said, things can happen …) Instead, I decided to fix the error with a plane. To do this, I marked the high section with pencil scribble, then removed the hinges and planed those scribbled high areas flat.

Now that my machining and joinery was completed, I moved to sanding the project smooth up through the grits, and applied three coats of oil-based polyurethane — this sort of project takes a bit of abuse.

All that remained to do was to bring it to my son’s apartment, which unfortunately meant carrying it up a few flights of stairs. Maybe the next time I offer to build something for him, delivery will not be included in the bargain.