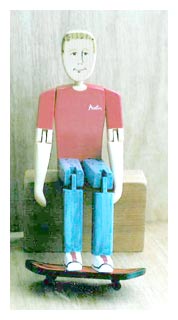

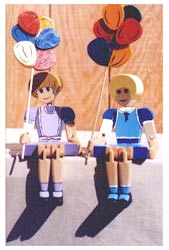

Imagine a place where you could order a handmade wooden doll with fully moveable limbs that looks like anyone you choose. Want a replica of your little girl in the school play, right down to her accurately colored costume? No problem. Need one of the Civil War generals for your favorite reenactment buff? Absolutely. Perhaps you’d fancy Shakespeare for an English teacher, Sherlock Holmes for a mystery buff, or an even smaller than life-sized Napoleon as a secret Santa gift for an overly ambitious co-worker. Whatever you can name, whether real or fictional, Henry and Linda Berkowitz, the modest makers of Endless Mountains Crafts, can craft a fully moveable articulated wooden doll to fill the bill. In fact, they have made over 300 different models over the years and are still adding new ones.

These dolls are a far cry from whittling, but that does lurk in the background of at least one of this pair of artists. “We work together to create the characters,” Henry explained. “I do the woodwork, and my wife does all the painting. Like all kids, I whittled with a penknife from the time I was young, and took woodshop in junior high. After college at Temple University in Philadelphia, I became a science teacher, but six years later, after getting disillusioned with the politics, I went to work in the family metal fabrication business.

“It took less than four years for me to realize I didn’t like metal as much as wood. In 1982, my wife convinced me we should move upstate to the rural area near the northern border of Pennsylvania. There were no teaching jobs in that sparsely populated area, and after trying a few things, we decided we could make a living with crafts.

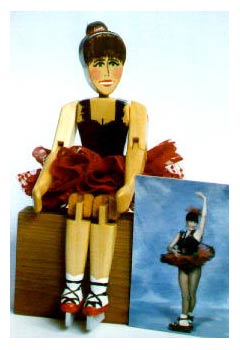

“Looking around and talking to people, we came up with the idea of making a jointed wooden doll. We spent a couple of weeks racking our brains for characters and came up with only five: an old salt fisherman, a ballerina, a lumberjack, a toy soldier, and I can’t remember the fifth.”

“We were renting a farmhouse with a weak second floor, so I had to keep the tools at the perimeter of the room. I made the first five. Some were supposed to sit, and some to stand, and they did. The second batch, however, did not go so well. The standing ones would fall over, and the sitting ones would not sit right.

“Making the pieces was not that hard, but putting them together so the joints move right but not too far was very difficult,” Henry confessed. “Being off by half a millimeter can mean the doll won’t work. It wasn’t until I got to about my 600th doll that I thought I was really getting it right. By then, I knew how to curve the parts, how to drill, and so on. I never made any jigs; even to this day they are all made by hand and by eye.

“I met one guy at a show who came up to me and said ‘I saw your dolls last year and went home and tried to make one, but never could.’ His friend told me, after the man walked away, that this guy had every woodworking tool imaginable, and couldn’t do it. That, I told him, is the problem. They are made by hand, and getting the trick to how they fit is what it is all about.”

Once the couple made their first few dolls, it was time to market them. “We went to a local craft show, the first of many, and sold only one doll at the show,” recalls Henry. “We were delighted. We went out to the local pizza joint and celebrated the fact that someone bought something we made. I built a few showcases and spread out, showing dolls to stores and gift shops in neighboring states as well as craft shows, and almost everywhere I went people would buy our dolls. Truth is, we never had any trouble selling dolls. We thought at the time they looked great, but compared to what we do today, I wonder how I had the gall to sell them.

“One of the first shows we did was a doll show. A woman came up and asked to order a doll for her husband, a railroad mechanic, that looked like and was dressed like him. We made it, and now we had six dolls. That happened again and again. Someone would say ‘Why don’t you have a Santa Claus?’ or ‘Why no clowns?’ As people asked for something, we’d add it to our collection, and the census grew by listening to the ideas that came from other people.

“Over the years, we have probably made and sold some 40,000 dolls. We’re still adding characters, because we are always being asked for something we don’t make. At shows I might have 250 dolls on display, yet people would tell us we still don’t have what they want. When people started asking for specific paint jobs, we moved into the custom design field, offering accurate eye color, clothes, glasses, suitcases; you name it. Most dolls are made to sit so people can sit them on a mantelpiece or book case, but some are made to stand on their own.

“I’ve never tried to teach anyone this. I don’t think most people would stick it out, and if I knew at the beginning how long it would take to get it down, I might have quit then. The fact that my first few worked, which was beginner’s luck, kept me going until I learned the ropes.”

That challenge has turned out to be an ace in the hole when it comes to competition. “A lot of woodworkers are out there making the same thing others are making, but we were lucky. As far as I know, I am the only one doing this sort of thing. Others have told me they tried and gave up. After 20-some years doing shows, I have never run across anyone else doing precisely this.

While doll making seems a rather proscribed field of woodworking, the reasons Henry and Linda stayed with it go much deeper than the wood itself. “There are many times in business when things don’t go smoothly,” Henry explained, “and you ask yourself why you are doing it. The thing I have appreciated most was that this career allowed me to be home when my kids were young. I was here when they got up and here when they got home from school. I could work whenever I needed to, but still got to go to all the special events in my children’s lives.”

That same devotion to his children would also result in a sea change in the business. “In 2003,” Henry recounted, “my daughter was diagnosed with leukemia. That took us away from the business, so we cut back substantially. We could simply not get motivated to make dolls, so I started working part-time as a counselor for at-risk youth. My wife decided she did not want to travel to all the shows, and took a secretarial job, but this year she decided we should expand a little bit and do a few local shows each year. The business continues, but it is now only a part-time venture for us, and currently most orders come through our web site.”

Still, once the bug bites, it is hard to ignore. “I feel I will probably make dolls the rest of my life,” admits Henry. “I like working with the wood, watching the grain, carving. We are very content with where we are right now with the business.”

Before I let him go back to his workshop, I asked Henry to recall the most unusual doll he was ever commissioned to make in his 20-some years in this business.

“A man who counseled alcoholics asked me to make a doll that would balance standing up,” recounted Henry, “but if you put a whiskey bottle in his hand, he would fall over.”