Adam Crowell might have been “musical most of my life — I was always tapping on things and stuff,” but his description of his childhood experiences with his hobbyist woodworker father was that, “I was always being drug into the shop by my dad, teaching me to do certain things.”

Although “I didn’t want to do it at the time,” Adam said, “now at this point in my life, I’m grateful that he did.”

Adam nowadays is putting his own musical talent together with the woodworking skills gained from his dad to create a business making and selling wooden drums. They range from six- and ten-note rectangular tongue drums to music tables and his own invention, the songa drum.

Despite a high school spent “beating on desks and stuff,” Adam himself played trumpet and guitar, but didn’t pursue drumming until he got into college. At that point, a professor who caught him tapping out a beat in class handed him a drum to keep rhythm. Adam became a percussionist, spending some time gigging in Los Angeles, where he became familiar with many small venues’ needs for percussion sounds.

He already had a background in aesthetics and design — the college where the professor handed him the drum was Savannah College of Art and Design — and wanted to get different sounds and know why a drum sounded like it did.

The now 29-year-old Adam spent a few years making drums for himself, and went into business about four years ago. He loves the infinite complexity available by changing the arrangements of the chords, or the scales, he said.

“They’re not just professional instruments,” he notes. “Anybody, regardless of musical talent, can pick up one of my drums and have it sound good. The way I group chords, you can mash your hand down — gently — and have it still sound good, and a classical composer can take it and make a beautiful piece [of music]. It’s simple, but you can continue to learn.

“My drums are simplicity and complexity in one,” he said. “I can make a specific sound, and I’ll make several drums for people with different tones.”

Although some instrument makers might swear by padauk, Adam says, “my favorite is canary wood. I like the sound; I prefer the cleaner tone.” However, he said, “It’s a personal preference — it’s Chevy or Ford at the end of the day,” and he doesn’t limit himself to one type of wood, also using padauk, mahogany, walnut and cherry, among others. “Some days, I’ll get really excited about one of the woods, and the way it sounds.” And, sometimes, one of the woods will be more difficult to work with, and it will take longer to make a drum with that material.

Adam doesn’t necessarily mind that, but he does note that he occasionally needs to take a break “and just take the drums out and play, get in touch with what I’m doing. I’ll find a piece of grass, or wherever I feel like being that day. It’s not terribly productive in the shop to waste 30 minutes drumming on an instrument.”

When he’s back in the shop, he identifies “attention to detail” as “the number one shop skill everybody needs to have. It seems dumb when you’re young to need to know everything, but when you make it a career, even things like that old saying ‘measure twice, cut once,’ it makes sense.”

As Adam goes forward in his career, he says, he would love to invent more percussion instruments. He’s already started on this with his mid-2010 invention of the songa drum. This brainchild, he said, came about because percussionists, in general, need to find other people to play with – “because if it’s just percussion, it’s just rhythm, no melody,” he said. With the songa, a name taken from a Swahili word meaning “move,” Adam has combined the rhythm and the melody in one instrument.

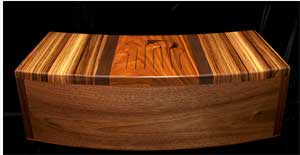

“It looks beautiful, but everything serves a purpose,” he said. For instance, one example of this three-panel curved drum is made with a middle section of canary wood, purpleheart inlays and zebrawood on the playing surfaces.”The far right and far left will give you a completely different rhythm” than other sections, Adam said.

Most of Adam’s other pieces at this point are tongue drums, with each “tongue,” or key, acting as part of a scale that can be played with mallets or by hand. Recently, however, he has also built a musical drum table. For all of his pieces, he applies a finish of tung oil, linseed oil and wax.

He’s included recordings of his drums on his website, but notes that, due to speaker technology, they don’t sound their best unless listened to via headphones.

“I make drums for everybody,” Adam said, “from children to 70- to 80-year-old women.

“I was out playing one day, and a lady walked by and called it a ‘smilemaker.’ Another lady called it ‘a gentle noise.'”