I mentioned yellow poplar last month in my post about the Southern yellow pines, so I thought it would be appropriate to follow up on that. Yellow poplar (Liriodendron tulipfera), or tulip poplar for most of us Southerners, is one of two trees in the genus Liriodendron. The other is a native of China. Neither are true poplars. True poplars are in the willow family of trees, which also contain the genus Populus (cottonwoods), and which is Latin for “people” and was also the Latin name for “tree.” (I could get confused, too, if I didn’t write all this stuff down.)

I mentioned yellow poplar last month in my post about the Southern yellow pines, so I thought it would be appropriate to follow up on that. Yellow poplar (Liriodendron tulipfera), or tulip poplar for most of us Southerners, is one of two trees in the genus Liriodendron. The other is a native of China. Neither are true poplars. True poplars are in the willow family of trees, which also contain the genus Populus (cottonwoods), and which is Latin for “people” and was also the Latin name for “tree.” (I could get confused, too, if I didn’t write all this stuff down.)

Deep breath; I’m almost through.

Liriodendron is a derivative of a Greek term for “lily.” Tulipfera, the species name, attempts to describe  the flowers of the tree as well, and they are tulip-like, so the Latin name for yellow poplar is either redundant, or an oxymoron, depending on how you look at it. Regardless, they do produce lovely blooms in the spring. Yet, few people ever see them as the yellow poplar tends to be tall, straight, and clear of lateral branches for a good distance up the tree.

the flowers of the tree as well, and they are tulip-like, so the Latin name for yellow poplar is either redundant, or an oxymoron, depending on how you look at it. Regardless, they do produce lovely blooms in the spring. Yet, few people ever see them as the yellow poplar tends to be tall, straight, and clear of lateral branches for a good distance up the tree.

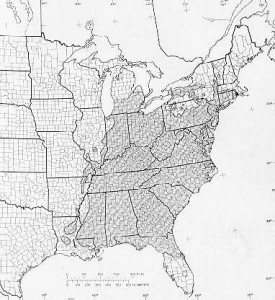

And I mean a really good distance. Yellow poplar can reach heights of 160 feet, making it the tallest of eastern American hardwood trees. It can also reach a diameter of 8 feet. The best and largest yellow poplars tend to occur along the Appalachians, but I commonly find high quality trees in the upper coastal plains of Mississippi and Alabama. For reasons only known by Mother Nature, yellow poplar never gained much of a foothold west of the Mississippi River. It is truly an Eastern tree as it occurs from Massachusetts to North Florida, across to Louisiana, and on the hills along the Mississippi River Valley and up into Michigan.

The most popular use of yellow poplar lumber is for interior parts of furniture, toys and other manufactured items. Many millions of board feet are used annually in plywood, trim, crates and pallets. The reasons it is so widely used in manufacturing are many, but not the least of them is how easy it is to work with. It is straight-grained (a result, no doubt, of its usual “straight-as-a-broomstick” growth habit), lightweight, and uniform. It also tends to be stable when dry and is fairly pleasant to work with when planing, drilling, turning, and painting it.

The other reasons it is so readily available and widely used are that it grows almost as fast as pine, occurs over a wide region, and the trees have few problems with rot, sweep, crook, knots, and twist. As a forester, I would consider it as almost the perfect tree to grow for lumber.

The other reasons it is so readily available and widely used are that it grows almost as fast as pine, occurs over a wide region, and the trees have few problems with rot, sweep, crook, knots, and twist. As a forester, I would consider it as almost the perfect tree to grow for lumber.

But all is not roses (or tulips) with yellow poplar. It may surprise many woodworkers to learn that yellow poplar ranks lower than most important American hardwoods when it comes to bending strength, impact resistance, crushing strength, shear strength, and tensile strength. It so highly regarded for many uses we tend to ignore these shortcomings. (After last month’s yellow pine post, I was asked by a friend of mine how I could mention yellow poplar (which he uses a lot) and yellow pine in the same breath. Well, these shortcomings are the main reason.)

The U. S. grows about 2,137 million board feet of yellow poplar and harvests about 30 million. So, it is truly a sustainable forest resource. It is my go-to wood for many of my woodworking projects.

Tim Knight