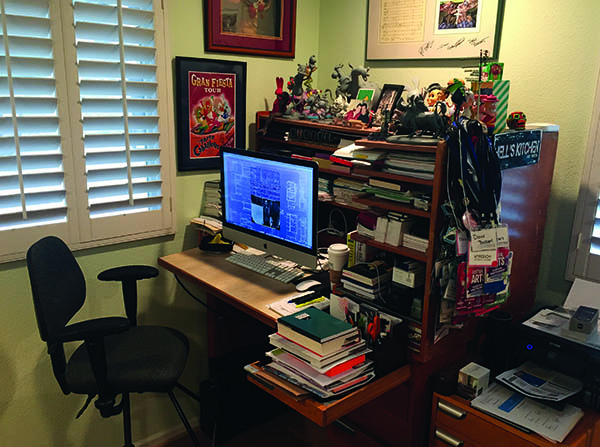

When Dave Bossert “retired” from Disney Animation Studios after 32 years, he received a parting gift: the Kem Weber-designed animator’s desk he’d been using for over three decades.

Weber, a mid-20th century designer and creator of the iconic “Airline” chair, was the architect and furniture designer for the creation of the Burbank, California, Disney studios complex in the 1930s. While Dave sat at the desk, now located in his home office, and worked on a book about one of the Disney films he’d worked on, it occurred to him that the Kem Weber Disney animation furniture itself was deserving of a book.

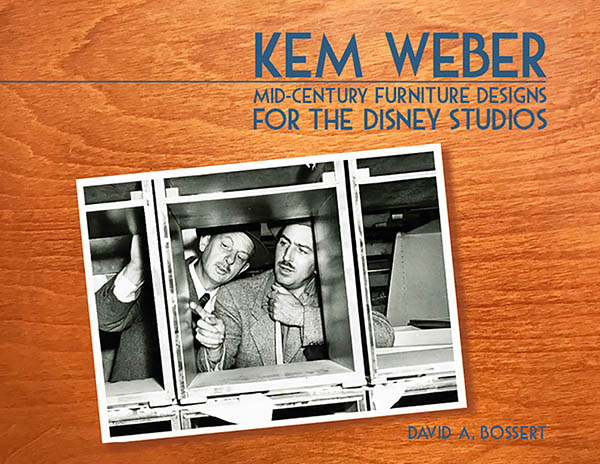

“Having worked on the furniture, having heard stories about the different things with the furniture over the years in conversations with colleagues,” Dave found himself uniquely qualified to be the one to write that book: Kem Weber: Mid-Century Furniture Designs for the Disney Studios (published by The Old Mill Press in 2018).

Weber’s furniture designs for the Disney studios encompassed a variety of pieces styled for particular jobs within the hand-drawn animation industry. “There’s an animator’s desk; there’s a background artist’s desk; there’s a layout desk; there’s a storyman’s desk. There’s all these different types of desks that have different attributes and features specific to that particular discipline,” Dave said.

For example, on the desks with drawing boards, a lever underneath the board allows for adjusting the drawing surface to any suitable angle. Also located underneath the drawing boards was a light box capable of illuminating multiple levels of animation paper; the brightness of the light box was also adjustable. “In some of the early Kem Weber designs, he actually had indicated that there was this whole elaborate foot pedal mechanism so the artist could use both hands to adjust the drawing surface angle by using the foot pedal, but from my research, I suspect that creating the whole custom foot mechanism was probably cost-prohibitive, and they just went with the straight-on lever,” Dave said.

A modular design allowed the original users to customize the desks’ lower section into the particular drawer or shelving configuration that suited them, with the upper sections based on their particular discipline. A recessed channel on the upper portion fit into a corresponding raised channel on the lower portion to fit them together.

“When you sit at one of these desks, you can’t help but wonder what legendary artist was sitting at this desk 50 years ago,” Dave said. “There’s something historical about it.” While he doesn’t know who had his own desk, some of the desks do have names of the previous users written on the underside of the drawing table. He does know the person who had his desk “was a smoker. Underneath one of the shelves is a three- to four-inch round nicotine stain.” Dave’s supposition is that the desk’s occupant had placed an ashtray on a lower shelf and, when dropping a cigarette into the ashtray, “the smoke just hit the bottom of the shelf as he was working so there’s this nice, dark nicotine stain, which is just sort of a wonderful part of the desk.”

A woodcarver himself (he’s been carving basswood wildlife sculptures for years), Dave was surprised to find out through his research that the furniture many people had assumed for years was maple was actually made from solid core birch plywood. That’s what’s listed on the original blueprints he discovered in the Kem Weber archives at the University of California Santa Barbara, and a closer look at the grain pattern on his desk – replicated in the photo used for the background of the book cover – seemed to confirm it.

The furniture was finished with a varnish that has acquired a golden patina over the years. There also appears to have been a beeswax application to the raised wooden track used for drawer slides, Dave said. He notes that he’s never reapplied any beeswax, but “the drawers slide out just perfectly.”

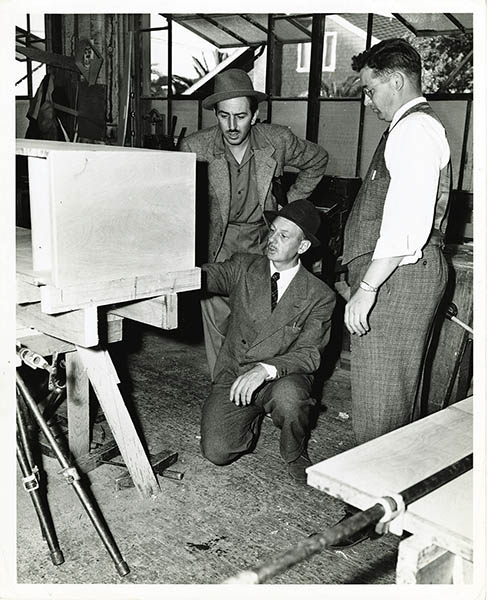

It’s entirely possible that Walt Disney himself was involved in such design decisions. Although Dave didn’t find much archival correspondence between Weber and Disney, “You can see there’s a bunch of photos in the book of Walt Disney with Kem Weber and Howard Peterson. Walt was very hands-on in meeting with Weber.” Peterson was from the Peterson Show Case & Fixture Co., Inc., in Los Angeles, the manufacturer of the furniture – and of the prototypes that preceded the final iterations, like the desk animator Frank Thomas used during the making of Pinocchio in 1940. Disney had asked for Thomas’s input in the original desk design; after he put the prototype to use, its rounded edges and painted finish were refined out of the final design.

“Weber was having his input on the design, obviously, but he was also translating Walt’s vision,” Dave said. He also notes that it’s possible to still see the influence of these design decisions and the streamlined Mid-Century Modern aesthetic in various buildings designed for Disney properties, including the parks and resorts.

As for the original animation furniture, when it was built in 1939, “The idea was the furniture stayed in the office. If an artist moved, he just packed up his personal stuff and went to a different office that had the same desk,” Dave said. Over the years, however, that’s not what ended up happening.

For instance, Dave remembers moving to a smaller facility while working on 1991’s Beauty and the Beast, for which he served as supervising effects animator. He took his desk with him, and “was happy I had a compact animator’s desk as opposed to the regular animator’s desk,” which was 16 to 18 inches wider than the compact version.

Other changes have occurred in the animation industry itself. “There’s a few of the desks that are being utilized at the studio still today, but for the most part, the animation industry has changed over to computer animation, and there’s specialty desks available for computers,” Dave said. “These particular desks were designed specifically for the hand drawn aspect of animation.”

After the book’s publication, he received a note from a director of operations at Walt Disney Animation Studios who said “he loved the book and it was so helpful because they had furniture pieces in their warehouse that they had no idea what they were. A lot of this furniture has just sort of filtered out of the company. They’ve given it away to artist who were retiring; they sold it; they had warehouse sales where they sold the furniture to artists.”

With a rising interest in Mid-Century design and the provenance of these furniture pieces, they’ve also become collectible, with some being sold at auctions for display pieces or repurposing. (Dave also notes in the book that, in recent years, the Disney company has instituted an annual inventory of the location of the remaining 100 or so original Kem Weber Airline chairs at the studios.)

“From my perspective,” Dave said, “I thought it was just an important piece of history to document.” He called the book “a labor of love. I think we all had a certain reverence for the furniture. I quote some people as saying, and I feel this way as well, that the furniture has a soul to it.”