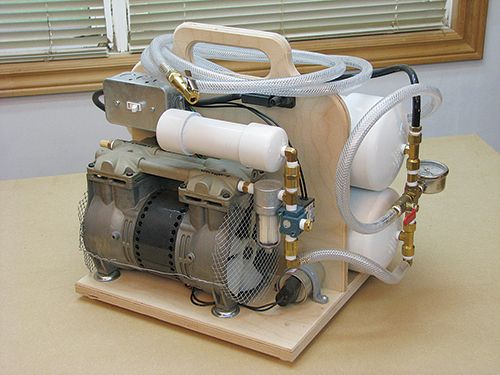

Having helped woodworking students of mine build a vacuum pump set up from a kit, I decided it was time to invest in one myself. I chose a kit with a 3.15 cfm pump, which will handle 4′ x 8′ veneer bags for flat work and 4′ x 4′ bags for moderately curved work. The kit I bought at joewoodworker.com came with all the main parts required. I simply built the wooden stand, supplied the PVC pipe and did a bit of wiring, all according to the detailed plans supplied with the kit. It resulted in a nice, tidy and mobile package.

I use a quality polyurethane bag, which is fairly expensive but offers good durability for professional use. For occasional use, a high quality vinyl bag will suffice and cost less.

Commercial Veneers

In this article, I’m using commercially cut raw wood veneers in a species called makore. At only 1/42″ thick, only light sanding can be done on the finished panel, not planing or heavy scraping. You can also cut veneer yourself with a good band saw (more about that shortly).

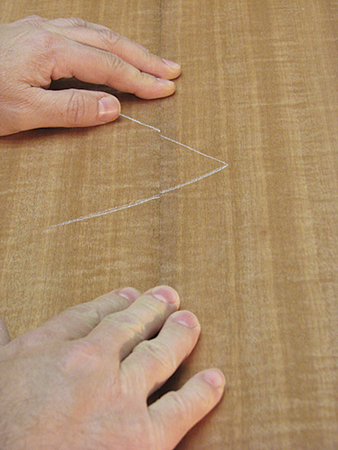

With commercial veneers, it’s as simple as laying out the veneer sheets in sequence and flipping over every other sheet to achieve a book-match. From a flitch of 24 sheets of veneer, I applied veneer to one side of an MDF panel using just sheet number 5.

The original veneer sheet was long enough to provide two lengths of veneer for my panel, so I simply cut the sheet in half with a veneer saw and rotated one of the halves for the book match. I didn’t even need to flip one sheet over. With veneer this wide, I needed only two pieces with one joint to cover the entire panel on one side.

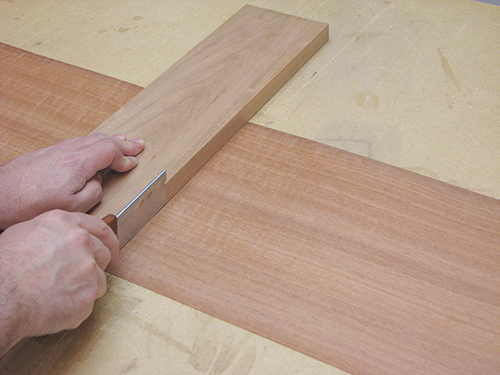

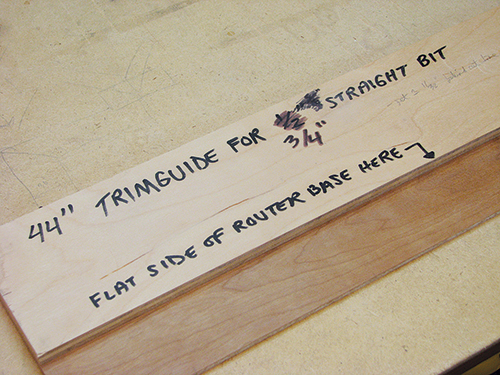

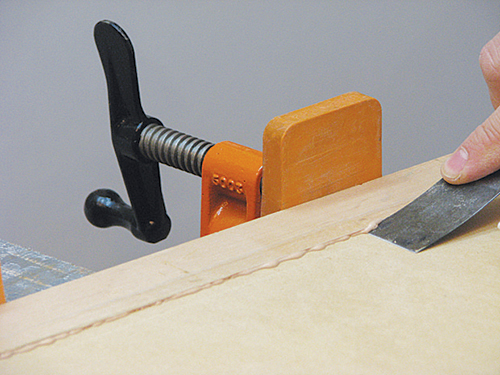

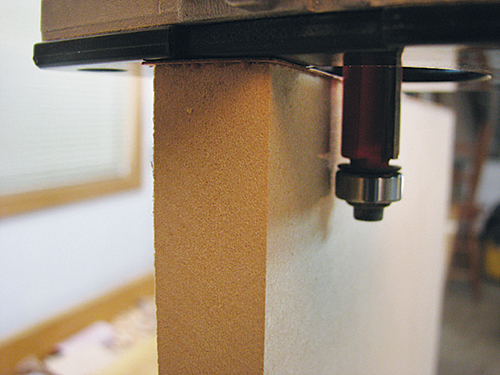

When using two or more pieces of veneer to cover a substrate, their aligning edges must be perfectly straight to avoid gaps (like a butt joint in thicker stock). I started by jointing the mating edges of the sheets I had cut from the larger original sheet using a common flush-trim router guide.

I sandwiched my two veneer sheets under a simple jig and on top of a sacrificial piece of 1/4″-thick MDF. By allowing the veneers to protrude slightly from the jig, it was easy to trim the edges with a straight bit in a router. To avoid tearout, given the tiny amount of wood being cut, you can safely climb cut.

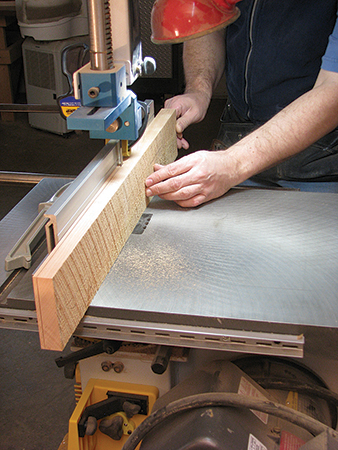

I can trim a whole stack of veneers at the same time with this method. There’s also an alternative method where I simply place the two veneer sheets against my jointer fence with a hardwood guide at the front. Then I joint the veneers and the solid board together. This works for shorter veneers like I’m using here, but the trim guide is best for long veneers that are unwieldy to handle.

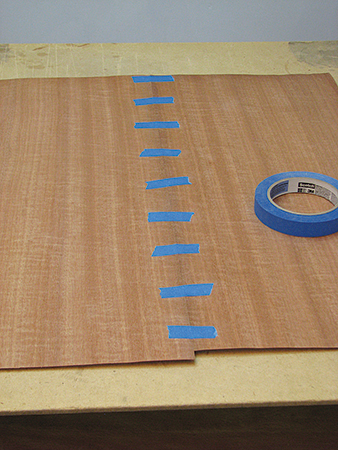

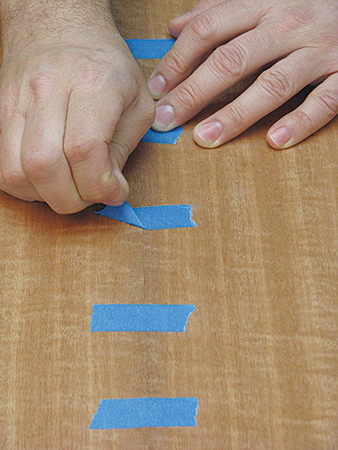

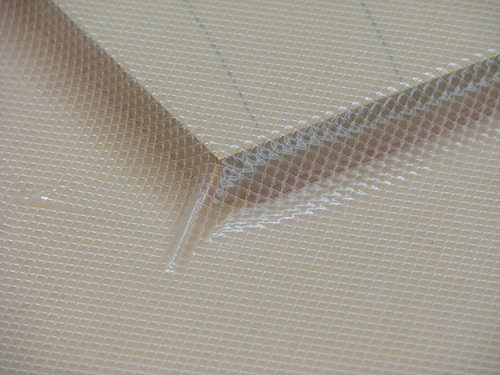

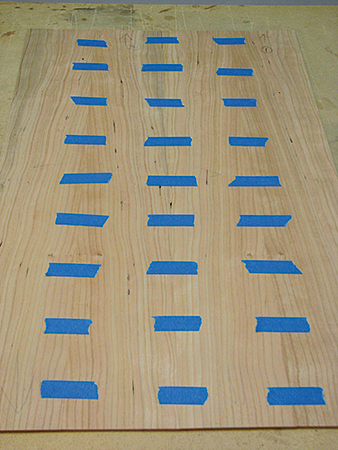

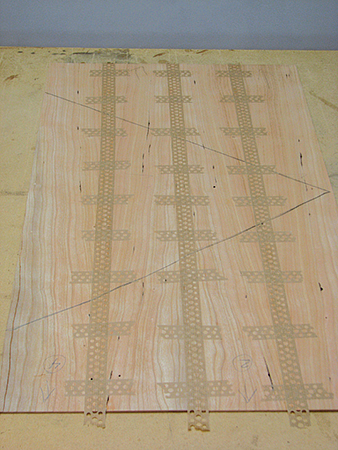

After jointing the edges, I secured the veneers together using blue tape placed across the joint every few inches on the back side. Then I applied veneer tape on the front side, first across the joint and then one long piece along the joint.

This tape has an adhesive on the back so I just run the back over a wet sponge before laying it down. With that done, an iron set to medium heat shrinks the veneer tape as it dries, pulling the joint even tighter. Now remove the blue tape from the back.

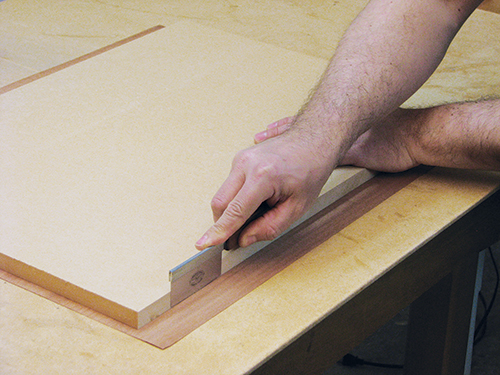

Because the veneer lay-up was larger than necessary, I trimmed the outer edges by placing the MDF core over top of it and trimming around the edges with the veneer saw.

The MDF core itself was oversized as well to allow for easy trimming after the glue-up. Sometimes the veneer will shift slightly on the core under vacuum pressure, so it’s best to leave some room for error.

In this case, I also veneered the front edge of the panel with a small offcut of the same veneer, using a clamping caul to distribute the pressure. The face veneer will hide the edge veneer joint.

You can use different kinds of glue for veneering, including plastic powdered resin, epoxy and even regular wood glue, depending on whether you are doing curved work, using paper-backed veneers or raw wood veneers, etc. For my purposes here, cold press veneer glue gives me enough working time (about 10 minutes) for simple flat panels, and it dries within a reasonable time.

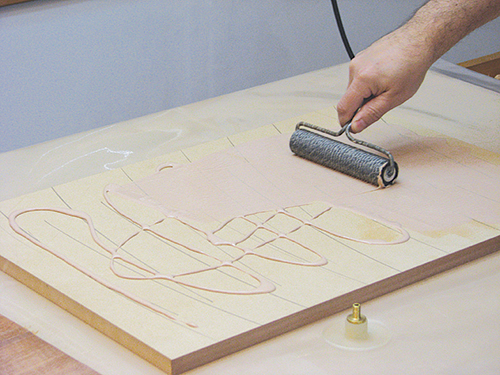

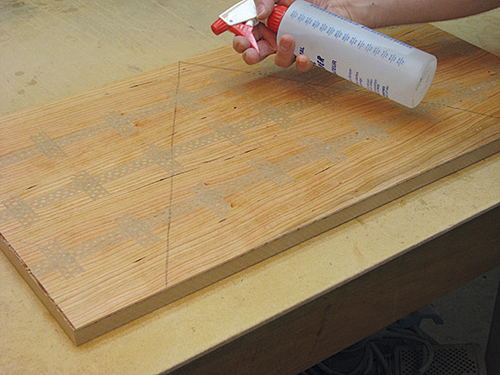

I sanded the MDF core with 120-grit sandpaper to knock off any surface glaze. This is not required when using a Baltic birch core. Then I covered the core with dark pencil lines to give me an idea of how much glue to apply with a 6″-wide glue roller.

The glue should be relatively heavy but still allow the pencil lines to show through. Apply glue only to the substrate, and spray the veneers with a light mist of water right after laying them over the glue to prevent them from curling. I taped the veneer to the core with blue tape to keep it in place, making sure it protruded slightly beyond the front edge band. The rear edge and ends can be trimmed to final size later.

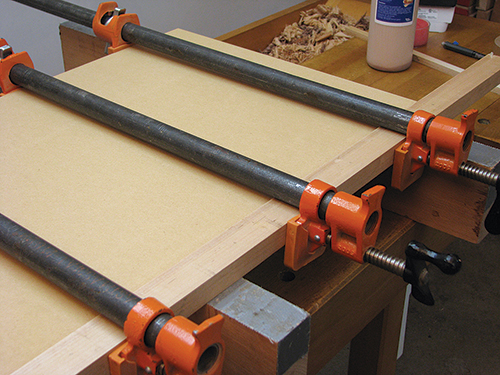

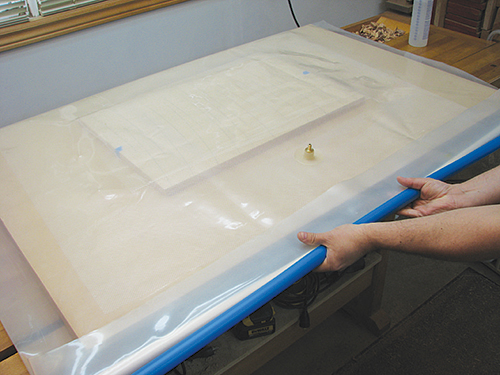

I placed the panel in the veneer bag upside down so the veneers are on the 3/4″-thick MDF platen in the bag. Don’t forget that you also need a backer veneer to keep the panel from warping. This can be done as a separate glue-up later with the backer veneer also sitting on the platen side. Or you can veneer both sides at once if you’re quick, placing the front face veneers on the platen (upside down) for the best quality glue-up on the show side.

Given that I used breather mesh on top of the panel, I didn’t need an upper platen, nor did the lower platen need to be grooved for proper evacuation of air from the bag. In the past, most people used both an upper and lower platen for flat veneering, although an upper platen can’t be used with curved work. With the use of breather mesh, though, one can eliminate the upper platen entirely, even with flat work. (I purchased breather mesh from veneersupplies.com.)

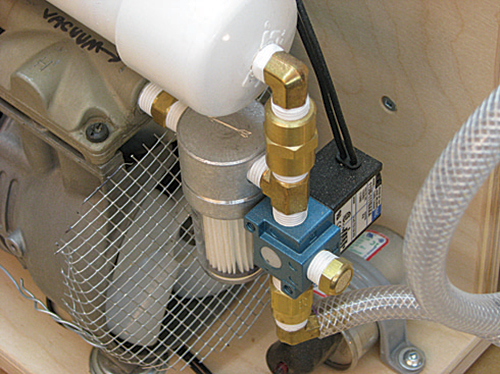

I’ve done various experiments to get around bleedthrough, which can occur when the vacuum pressure forces glue right through the veneers, interfering with stains and finishes. From my experiments, I’ve had great success setting the vacuum pressure to just 17 Hg (inches of mercury) for the first 10 minutes and then increasing it to 21 Hg for another 30 to 40 minutes. For more porous veneers such as burls, it’s best to use a powdered plastic resin glue, which really reduces bleed-through.

Remember that the glue-up should not remain in the bag longer than an hour when using cold press veneer glue, as it needs exposure to air for the glue to dry properly. Also, keeping the panel under vacuum for too long with a water-based glue can cause mold spores to grow, producing unsightly stains.

Shop-cut Veneers

Working with shop-cut veneers isn’t that different, except that you cut them yourself. Start by finding a piece of lumber that has no grain reversals or only very minor ones.

Choosing stock with grain switches and unusual figure will cause all kinds of tearout when jointing and planing, unless you have helical cutterheads or a thickness sander. For really highly figured stock, I prefer commercial veneers since they can be flawless right out of the box. Sometimes I need to use liquid veneer softener to flatten badly curled or wavy veneer.

Joint one face and one edge of the stock and bring the second edge to final width with a table saw and thickness planer. Then cut a sheet of veneer off on the band saw, rejoint the face of the blank, and cut another sheet of veneer. By jumping between jointer and band saw, you can cut multiple sheets of veneer that are already smooth on one side and both edges (you’ll still need to rejoint edges before taping to get really tight joints).

A few quick passes through the thickness planer with an auxiliary bed brings them to final thickness. I’d suggest veneers at l east 1/16″ thick, though I prefer 3/32″, which allows me to do some hand planing an scraping on the finished panels if necessary.

Be sure to make similar thickness veneers for the back, using a less expensive species if you like. I don’t recommend 3/32″ face veneers and 1/42″ commercial backer veneers because the panel needs to have a balanced veneer thickness to resist warping.

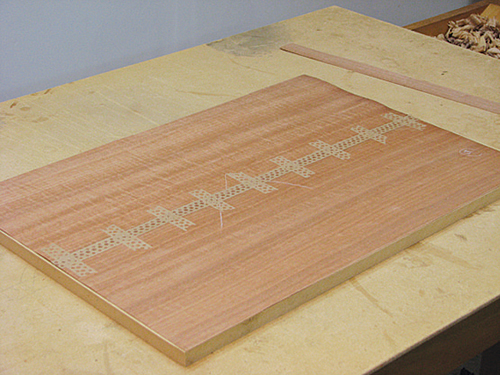

The panel I glued up here is no different than the one with commercial veneers except that I used narrower pieces requiring three joints. I also flipped every other piece of veneer to get my book-match. Other than needing a lot more tape, the process is much the same.

In this case, I didn’t veneer any edges, which wouldn’t be necessary when making a panel for a frame-and-panel door, for example. I also used a Baltic birch core instead of MDF, which lightens the weight and eliminates the need to sand the core material. Another suitable core material would be particleboard. Baltic birch is nicer to work with, but not as flat and consistent in thickness as particleboard and MDF.

Conclusion

While I’ve used veneered plywood my entire career, I only did my own veneering on occasion on very small panels using lot of clamps and clamping cauls.

Owning a vacuum pump certainly makes veneering easier and opens up a lot of possibilities with exotic, highly figured veneers, such as pomelle figured sapele panels, which are just gorgeous.

As an added benefit, I also regularly use the vacuum pump to glue two 1/4″ sheets of veneered plywood back-to-back when I need 3/8″ to 1/2″ ply. I find that 1/4″ and 3/4″ ply is widely available, but in-between sizes are harder to find. Give a vacuum pump a try, and I think you’ll be hooked in no time.

Hendrik Varju is a fine furniture designer/craftsman who provides private woodworking instruction, seminars and DVD courses. His business, Passion for Wood, is located near Toronto, Canada. See www.passionforwood.com.