In last issue’s eZine, Rob mentioned his upcoming judging duties for the woodworking entries at the Minnesota State Fair – and wondered if, and how, eZine readers have gone about teaching woodworking to the next generation.

For several readers, it’s the grandchildren’s generation with whom they’ve been involved in woodworking. – Editor

“I have two great-nephews, ages 5 and 7. I have been making toys and games for them for their birthdays and Christmas since the oldest boy, Ewan, was a year and a half old. When Ewan was younger, he became very emotional when he saw broken or damaged tree limbs until I convinced him that really cool things could be made from the broken parts of a tree. His first experience in the workshop was when he was three years old, and I think he has caught the woodworking bug. Each time we speak he has come up with a new creation to make when he and his family are visiting, from spaceships to buckets to whatever his busy brain conjures up. I encourage him to draw up plans for said project and we will work on it on his next visit. And when he and his family do visit, a project in the workshop is a requirement. The younger boy, Xander, joined us in the workshop when he was three as well. He is not quite as interested as Ewan, but I will be working on him! Both boys are currently involved in helping their parents build a tiny home. Maybe their mom and dad have a bit of the woodworking bug, too!” – Sandy Syring

“Having been blessed with an even dozen granddaughters, I started woodworking for them by turning rattles and other small things when they were still tiny. As they grew older and I would overhear comments about doll things from furniture-houses, I decided to preplan our eventual trips to the shop. I would choose which patterns we would use and cut many of the parts needed in advance. I think the key is not spending too much time on a project, in one sitting, with little ones, (with short attention spans). This can change what should be a fun project to a boring one. I tried to keep the sessions short and made sure they were involved in the finishing (if not too messy). So far, so good.” – Marlin Schiefert

“I’ve done two projects with one grandson, but none with the other three grandsons or the four granddaughters. Both were done for a 4-H competition and each took almost a week to complete. The first was a square sofa end table in cedar, when the grandson was 12. The other was a student desk built a year later. To avoid a lot of glue-up time or edge treatment of plywood, it was mostly made from 12″ and 24″ wide pre-made fir panels bought at the local home center.

“In both projects, I’d explain a step, perform it once, and then supervise while he did the same operation on other pieces. Between the two projects, we used all the big power tools (planer, joiner, table saw, band saw, drill press) and most of the small ones, too (router table and handheld, sanders, drill, clamps). I kept the joinery to simple dado and rabbet, all glued, with screws in most and using pin and brad nailers on a few. If I want to get more of the grandkids involved I need to come up with simpler projects. Unless they’re motivated by something like this 4-H competition, it’s hard to keep their attention for more than an hour or so. Of course, my wife will tell you I can’t build anything in an hour or two.” – Henry Burks

“I have two marvelous grandsons (aren’t they all marvelous?), aged 3-1/2 and 2-1/2, who have already show keen interest in ‘helping.’ We started early with the kitchen: cookies, pancakes, and the like. And, I’ve already had the older one help me glue up a box. From here out for the next few years, I plan to prepare ‘kits’ for toy airplanes, fire engines, and anything else I can dream up, that we can assemble and decorate. Maybe we can gradually work in manual tools like eggbeater drills and braces, clamps, a plane or two, and screwdrivers in four or five years. You never know … it just might work.” – Dan Else

For some readers, it has been through organized groups that they have introduced their family members, as well as others, to woodworking. – Editor

“When my oldest daughter was 8, we started in 4-H woodworking (I was still a novice at the time, myself). She turned 40 last week. Through a dozen years of her and her younger sisters, we made an annual pilgrimage to the Ohio State Fair for state competition. Once they were done, I started as a judge there myself, where I have been every year but two since. (One of those two I’d just had surgery and the other, said daughter, staying with me over the summer, just delivered twins.)” – Keith Mealy

“I am a member of North Carolina Woodworker, Inc. We are an online woodworking group that teaches woodworking. We are a 501c charitable organization. We purchased a trailer, lathes, scroll saws, a drill press, band saw and a variety of hand tools and sharpening tools. We travel around the state and give classes and/or demos. We have taught Wounded Warriors, firemen, Girl Scouts, Boy Scouts. We also demonstrate at local festivals allowing people to ‘make something!’ I am the events director, and scroll saw specialist, and I love this group!” – Roberta Moreton

“Rob, I have made a few small items alongside my two granddaughters. But, they are a little hesitant to work with some of Grandpa’s tools in the shop environment. However, Lowe’s® and Home Depot have weekend programs where you can take the kids. They provide free kits that are assembled there. They provide the materials, tools, glue, paint, etc. They also award pins and certificates. My girls have put together many of these and they enjoyed every one. They still have most of them and we donated a few others. Some of the items are useful, some are toys, and some are holiday based. They are older now, but we still talk about their woodworking experiences at those retailers.” – Rich Franks

“For the last six years, I have been working as a staff person in the Chicago Area Council Cub Scout day camp program. It is three to five days of working with Cub Scouts, and I have been doing the craft station. This is anything from leather to wood. At least one day is a serious wood project. We have done toolboxes, picnic caddies, trophy stands for pinewood derby cars, etc. The parts are precut, (my job); the rest is teaching them safety, proper assembly and technique. The kids get a charge out of building something, and my hope is that they learn a little while having fun. The biggest challenge seems to be teaching these little kids how to hammer. The most gratifying part, was at this year’s day camp a mother came up and thanked me for teaching her son how to hammer and use tools because this year her son was able to assemble his project on his own and help others. It doesn’t get any better than that.” – Jamie Goodwin

For some, however, they just haven’t found a way to spark the interest. – Editor

“I tried to get some 4-H kids interested in some projects, including my own kids, but to no avail. Electronic devices are a formidable opponent for this generation. I work in the woodshop a few times throughout the week and I can’t even get my own kids to come down to the shop in the basement to see what I’m doing. If you hear of, or find something that works, please let me know. I wish I had better news or more positive experiences to share with you, but I don’t.” – Kevin Courtright

And some have taken their own negative experience with the previous generation’s teaching style and turned it to a positive for subsequent generations. – Editor

“This might not be quite what you had in mind, but it’s heavy on my heart to share it:

“Back when I was a kid, my dad had no patience with me when it came to woodworking. The words I remember him saying were, ‘You don’t know what you’re doing; get out of the way and I’ll do it.’ I realized later in life that he was not much of a teacher either – he’d hand me the electric drill and point to where he wanted me to drill without explaining how to hold it or that it could jerk out of my hands when it bit into the wood. So as you can imagine, I came to believe that I truly didn’t know what I was doing, so it was best just to stay out of the way. There was no joy or pride in any wood craft I undertook, only a sense of how useless it was for me to even try.

“It took me a long time as an young adult to teach myself how to do things, and I had to adopt an attitude of ‘I’ll prove you wrong – I can do it.’ And while I am no master craftsman, I take a lot of pride in being able to build anything I set out to do. But I vowed not to be like my dad when it came to teaching my own son. So when my son’s Cub Scout troop was building birdhouses, I demonstrated the drill to each boy:

‘Here is how you hold it, with one hand here and one hand here, be sure to hold on tight when the drill bit digs into the wood.’ Each boy learned that they could do it – even the ones that were most reluctant to try. They all succeeded in drilling their hole in what would be the front of their birdhouse.

“Having come down the ‘other road,’ I feel like preparing kids to succeed beats setting them up for failure, hands down. Now, I’m not sure any of these scouts will go on to be master craftsmen, but hopefully they will all have the self-confidence to take on a woodworking project if they want to. And it makes me feel pretty good that I could pass on to them something I didn’t have when I was growing up!” – Tim Gaertner

This woodworker shared her memories and perspective of the way woodworking skills were passed on when she taught in Iceland. – Editor

“A long time ago – about twenty-some years – I spent several years in Iceland teaching English and whatever else I was at least somewhat qualified to teach in a rural elementary school. Over there, elementary school runs from kindergarten to 10th grade, and the shop curriculum starts in the first grade. The attitude towards kids and tools is quite different to that in the U.S. While the majority of the population lives in one of the handful of centers that are not just villages, parts of Iceland are so remote from any services that people who live there have to be jacks-of-all-trades in order to live safely and comfortably. (That is not unlike here in Alaska.) They start learning hand skills very young. At the end of the 10th grade, everyone is expected to know how to cook a simple meal, knit a hat, sew a seam, fix stuff, and build simple structures.

“One year, the school in our little seaside village found itself in need of a shop teacher. The whole community had use of the school’s shop outside of class time, and I was a pretty familiar figure among the tools and sawdust. Since I was already on the school payroll, I was handed a curriculum and warned not to let anyone hurt him/herself too badly. The little kids’ goals included becoming familiar with hand tools, following directions, and using a few simple power tools with my direct supervision. First graders made “flowers in pots” out of thin MDF, dowels, and pre-cut plywood pieces. They learned how to use a simple handsaw, a coping saw, try square, ruler, sandpaper, glue, hammer and nails, and paint. Each child got to use the drill press to put a hole into the top of the box that made the “flower pot.” Every mom in the village had at least one of these flowers on a shelf; some had a whole garden worth.

“Projects got harder and harder as the kids aged, and usually a lot of kids dropped out when the class became an elective in the eighth grade. That was OK, as everyone had had at least six years of shop class under their belts and could at the very least build a square box. I had only a handful of tenth graders, but all of them were very skilled already. They were expected to be able to design and make slab-built (plywood or particleboard) furniture in the IKEA-type style that is made of all straight lines and fancy fasteners. After that they could pretty much make whatever they wanted to: electric guitars, built-in cabinetry, tool and gear cases, computer desks, and so forth. My own daughter made a small canvas and wood strip canoe. Each of these advanced projects required shop drawings and a budget, which the kids hated at first but appreciated, mostly, by the end of the class.

“I loved teaching these classes. The ancillary learning was at least as important as the hand skills. Kids had to apply arithmetic, know when to ask for help, learn to be neat and efficient, clean up, help one another, plan the order of work, and allocate their time. The products the kids made were clear proof of how well they had learned these skills – or not, in a few cases.

“I wish that the U.S. could find it in its collective heart to allow kids to learn to use sharp tools and heavy hammers. I think we would all benefit.” – Lou Heite

And this one shared a different perspective of passing woodworking along the generations: she began woodworking at age 78 – inspired by her mother. – Editor

“Interesting article about woodworking and the next generation. I’m working on an older generation.’ I guess they don’t have ‘shop’ in schools anymore. That’s a shame. All of my mother’s four brothers were shop teachers. And my mother, when she was in her 50s, took adult ed shop classes and made a beautiful mahogany bookcase, which has been handed down to my son.

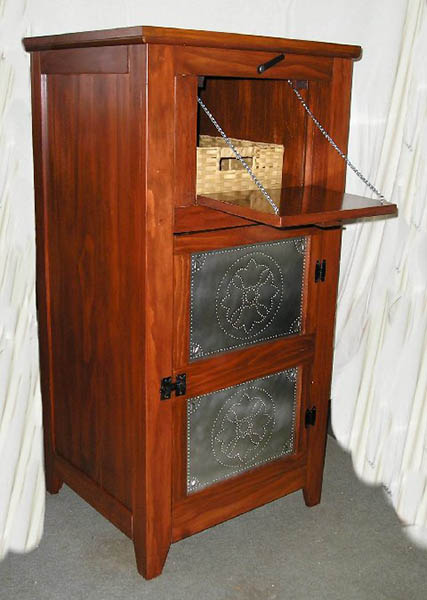

“Must be in our genes, ’cause a couple of years ago I said, ‘I think I’ll make an Arts and Crafts coffee table. I think I’ll make a sofa table. I think I’ll make a pie safe. I think I’ll make a jelly cupboard.’ So, I read a lot, went out and bought a Delta contractor’s table saw, added other tools as needed, and — did it. Designed and made a piece every year, starting when I was 78 years old, and gave them to the kids for Christmas: one piece, one kid, a year. All but the stool and coffee table have secret compartments.

“The kids said, ‘Where did you get this?’ I told them I made it. They said, ‘You did not !’ So little faith… Some of my pieces are maybe not perfect (I’m still struggling with perfect reveals), but pretty good for a self-taught old lady. – Joan Hogan