These days, dovetail jigs are about as common to a woodworker as table saws, but 30-some-odd years ago, the situation was quite different. You either cut dovetails by hand (the typical method at the time) or you picked from a very limited number of template-style router jigs to do the job. David Keller sold one, and so did Sears, with fixed pin and tail patterns. Then, along came Ken Grisley, founder of Leigh Industries, and a revolution in dovetail jig technology followed.

But that’s getting ahead of the story.

Recently, Matt Grisley, Ken’s son and president of Leigh Industries, took time to flesh out the history of Leigh Industries in much more detail.

“Our family emigrated from England to Victoria, British Columbia, in 1975. Dad was a fiberglass-and-mahogany boat builder — a business he had started with his brothers back in England — and he also owned an automotive repair business he bought from my grandfather. Boatbuilding was my father’s first exposure to woodworking, outside of school. But economic times were tough in the mid-1970s in England, so he sold all of his tools and the businesses and moved our family here for better opportunities,” Matt recalls.

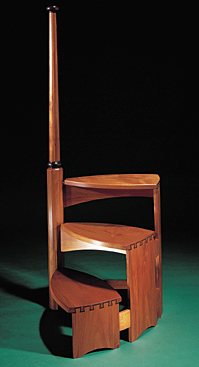

Ken took a job as a costing clerk at a sawmill in the little town of Quesnel. The family had sold all of their furniture to make the transcontinental move, so Ken decided to build his own furniture instead of buying it. First there was a kitchen table and chairs — humble but sturdy designs, in Matt’s recollection — then a sofa made from 2x6s, plywood and cushions. Ken’s interest in woodworking grew, and he started reading books by James Krenov and Tage Frid in hopes of building nicer pieces himself. He was inspired by their use of dovetails so he tried the hand cutting process, building a record player stand and a bedside table for Matt’s younger sister Kerry. Ken got the “hang” of hand-cutting, but not without a good deal of sweat equity. That’s when the pivotal moment came.

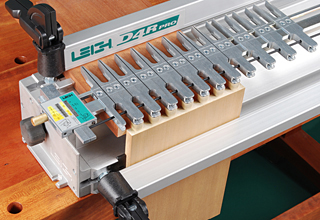

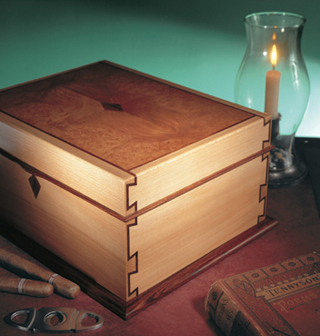

“Dad got frustrated with sawing and chiseling dovetails. He thought there had to be a better way than that. He was aware of the Keller Dovetail Jig, but it was a fixed-template system. What he wanted was the ability to vary the size and spacing of the pins and tails like he’d seen in those books. And he wanted to do it with a router,” Matt says.

Grisley believes that if his dad had actually bought a Keller jig back in 1980 or so, Leigh Industries might never have gotten its start. But the elder Grisley never made that purchase. Instead, he cut some jig fingers from Masonite on his table saw and screwed them to a 2×4; the jig routed pins on one side of the 2×4 and tails on the other. But, unlike other fixed-pattern commercial jigs, Grisley’s answer to variable spacing came from being able to unscrew and move the fingers wherever he wanted them. It was a somewhat crude first prototype; little inaccuracies in the Masonite edges translated right into the dovetail joint. Still, it was a start. “My dad saw promise there…’Hey, maybe there’s something to this!'” Matt says.

Around this same time, Ken worked a second job in a machine-tool company for the mining and forestry industries. Those machinist skills helped him build a better prototype to take the Masonite-and-2x jig to the next level. This time, it was machined aluminum and steel bar, and the new version proved a couple of things to Ken: variable spacing could indeed be possible for router dovetailing, and the accuracy would be easy to accomplish by better manufacturing. But the nagging question remained: if he mass-produced the first variable-spaced dovetail jig, would anyone buy it?

“My dad definitely has an entrepreneurial spirit, and it was there right from the start. Around 1980, he contacted a product manager at Sears, because it was tough to do much in the way of broader market research on woodworking tools at that time. Dad asked the guy how many routers Sears sold in a year, and this fellow told him a million. A million routers a year! Dad thought, if he could sell even 10 percent of that number in dovetail jigs, we’d be rich beyond our wildest dreams!”

So much for market research. Ken saw opportunity in that response from Sears. It was time to start a company and make variable-spaced dovetails a reality for more woodworkers. Ken and his wife, Joan, took all the family’s available funds and invested in a mold to create die-cast fingers for the first production Leigh dovetail jig: the Model TD515. He named the company after their English home town of Leigh-On-Sea and opened it in a two-car garage that didn’t even have a door to seal out the winter cold. Modest beginnings, surely, but a revolution in dovetail jig technology had begun.

Matt recalls some growing pains in the first few years of Leigh Industries. The company lost money on their first die manufacturer, which didn’t get the mold started on time. The second mold maker not only did a better job of keeping production deadlines, but continues to make the company’s molds to this day. The TD515 originally was designed to work with 15-degree dovetail bits. Woodworkers soon requested that the jig work with 14-degree bits instead. That required a new mold and more investment, but the former 515 evolved into the TD514 to accommodate the bit change. A recession hit in 1982, which slowed things down as well. Still, mail-order companies were eager to get their hands on Leigh’s new dovetailing technology. “My dad would jump on a plane and fly to these vendors to give his demonstration. Once they saw how well it worked, they gave him orders on the spot,” Matt recalls.

The jig took off with consumer woodworkers in a brisk way, even though there were limited advertising avenues by today’s standards and expensive toll-free phone costs. “In those early years, Dad advertised in Fine Woodworking Magazine, and we would provide our informational brochures, videos and (eventually) DVDs for free…Over time he accumulated a database of customers, and we would market to them whenever we had a new product to introduce.” Ken’s business venture began to see some positive returns.

Matt joined the company fresh out of high school as Leigh’s first “official” employee. “I had no aspirations to go to college…When I told my folks that I was considering firefighting, I think their fear about that option made the decision to hire me really easy,” Matt quips. He spent his time assembling jigs or traveling with Ken to do trade show demonstrations. Those appearances and time with woodworkers led to many, many more jig models and innovations since. The company’s “D1258” series dovetail jigs in the mid-’80s ushered in another revolution: the first jigs on the market that could tackle both through and half-blind joints using the same adjustable guide fingers. Then came the Multiple Mortise and Tenon Attachment, a replacement finger assembly that fit on the dovetail jigs. It enabled variable-spaced tenons to be milled on the ends of wide panels for joining shelves or partitions to mortised casework.

The Leigh D3 Dovetail Jig in the early ’90s provided fast-acting cam clamps for locking workpieces in place, another patented evolution from Leigh. Around this same time, Ken also invented an F1 template for making finger and box joints (also patented technology) and a Variable Guide Bush System with tapered bushings that could be screwed in or out to precisely adjust the fit of box joints during routing.

In the last two decades or so, the company has developed its FMT Pro Mortise and Tenon Jig as well as a D4 line of dovetail jigs with color-coded scales, improved dust collection and now single-pass half-blind dovetail capability. A Super Jig dovetail jig line, developed about four years ago, offers variable spaced half-blinds and box joints for woodworkers that need a more affordable solution for getting into jig-made joinery. There’s also a value-oriented Super FMT Jig.

All in all, Leigh’s corporate timeline traces a rich history of product development, and it’s all remained focused on Ken’s original goal of adding versatility and creativity to joint-making. Ken is still very much involved with the business. “Dad’s got a weird and wonderful mind…he comes into the office about three days a week these days. Who knows what he’ll come up with next?”

Leigh Industries remains a lean organization at around 20 employees, operating out of an 11,500-sq.-ft. facility in Vancouver. Matt admits that the current economic downturn has made business more challenging in the past couple years. But he adds that there’s also competition from what he calls the “electronic phenomenon”: new cell phones, hi-def television, other gadgets, Internet access. The monthly cell, cable and satellite bills from these devices have stretched disposable incomes that much thinner than before the recession. It can be tough for a companies like Leigh that rely entirely on the hobbyist woodworking market. Even so, Matt says the company has seen recessions come and go. They’ll ride this one out, too, and remain committed to evolution and revolution in new product offerings. Some are in development right now.

“I’ve told Dad that when I stop finding this work interesting, I won’t do it anymore. That day sure hasn’t come yet. Every day offers new and interesting challenges.”