Although Chris Hall makes furniture and other items, the aspect of working with wood he loves the most is Japanese timber roof work – even if he did pass up the chance to have an apprenticeship in a Japanese temple’s carpentry shop. (He’s got his reasons for that.)

“One thing I love about Japanese architecture is roofs; the spaces under the eaves

are very dramatic and beautiful,” Chris said. “My greatest love is Japanese timber roof work, but opportunities to do it don’t often come along.”

Instead, he tries to apply a timber framing mentality to his furniture pieces. Starting with his first furniture commission – a 9-foot L-shaped mahogany reception desk for a doctor’s clinic; he received the job after the doctor he was seeing for a shoulder problem saw his Timber Framers Guild T-shirt and asked if Chris did carpentry – “I’ve taken those aspects I like about timber framing and brought them to furniture.”

That includes making pieces that rely on joinery, locked together with wedges and pegs, rather than adhesives, so that they can be assembled and disassembled easily. His earlier furniture pieces used a certain amount of glue, Chris said, “but I’ve gone to ‘How far can I go? Can I make this project without recourse to adhesive?’”

One reason for this choice, Chris said, is to make things easier to fix down the line. “Families have different cultures and in mine, it was assumed that if something was broken, you would take it apart and fix it. That was normal to me. Having worked on different things, like fixing a lawnmower, or a car or a bicycle, the aspect of finding things that can’t be fixed” – such as pieces welded together – is “annoying,” Chris said. “It’s an aspect of disposable culture, and that bugs me.”

On the other hand, if something was easy to disassemble and repair, then, “Whoever made it thought ahead to me, and made it so it can be taken apart and lubricated and greased or whatever. They had respect for me.” Chris wants his pieces to show the same respect, both for future users and for the wood they came from.

“Wood is a limited resource, and if I design a piece, for sustainability, it should last at least as long as the tree I got the wood out of. Like if it was a 100-year-old tree, it should last that long,” he said.

Right now, Chris is working on a Japanese gate for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and is “up to my eyeballs in Port Orford cedar.” In general, he said, he prefers West Coast softwoods like sugar pine, Port Orford cedar and Alaskan yellow cedar for architectural uses.

When it comes to furniture, however, he tends to use tropical hardwoods. “As I delved more into furniture, I developed an interest in Chinese Ming furniture. I think it’s the finest furniture ever made,” Chris said, citing its design, easy assembly and disassembly for portability, peg joints without glue, and extremely hard wood.

Wanting to emulate that style, he likes to choose woods with a similar toughness, oiliness and resilience to the woods from the dalbergia (rosewood) and pterocarpus families that were used in the pieces from the Ming era.

“I do a lot of work with bubinga and cocobolo,” Chris said. “I love them for their beauty, but they challenge me in their working qualities.” Cocobolo breaks easily in small sections and, while some of the shapes Chris wants for his joinery require considerable hand cutting – and he prefers to use hand tools when working with softwoods – when it comes to these woods, he’ll finish the surfaces by hand planning, but otherwise tries to avoid the hand tools as much as possible “I’ve got carbide-tipped everything: saw blades, router bits… When it comes to bubinga, ripping a 15” wide board with a hand saw is not a prospect I’m interested in.”

“It’s a little at odds with what most would perceive to be Japanese tradition,” but, Chris said, “they’re not in time warp.” He spent several years of the 1990s living in Japan and, when he visited the carpentry shop of an Osaka temple building company, “I thought it would be like a scene out of a 1500s print.” Instead, he said, modern Japanese shops use modern equipment, including things like “a CNC – then, half an hour later, the guy’s out there using a hand saw.”

His visit to the temple carpentry shop came toward the end of Chris’s time living in Japan. He traveled there thanks to the work of the Canadian ambassador (Chris is originally from British Columbia), who was visiting Japanese areas with Canadian connections. The temple carpentry business has been around since the 1400s and, when they offered him an apprenticeship, “I thought about it very strongly,” Chris said. “It’ surprising to some, but I decided not to follow it.”

That’s in large part due to his experiences with another traditional Japanese craftsman, a swordsmith named Watanabe. He originally went to Japan in part due to his interest in martial arts. Once there and working as an English teacher on Hokkaido, the northernmost Japanese island, Chris made a connection with a swordsmith who was in the process of setting up within a new forge in a public display space for traditional crafts, including blacksmithing. Most of his duties “revolved around me chopping charcoal with a little hatchet,” said Chris, who at the time was looking for something to fill his days – his English teacher job was only keeping him busy about 10 or 12 hours a week.

At some point, he noticed that a cabinet in the swordsmith’s house had a piece broken off it. “I said, ‘I could probably fix that.’” Chris did a good job fixing the cabinet – and that displeased the swordsmith. “It’s a Japanese attitude that you can’t be good at two things: you have to choose one thing, and that’s what you do with the rest of your life. Total devotion to one thing.” The swordsmith gave Chris an ultimatum: an apprenticeship with him, or woodworking. Chris chose woodworking – and that was the last time he helped at the forge.

He still, however, had about a year and a half left on his teaching contract, and some empty hours in the week to fill. Luckily for him, something else that was sitting empty was a well-equipped woodworking shop in the local school district’s junior high.

After receiving permission to use the shop, Chris got offcuts from construction sites and books on Japanese carpentry and “started emulating what I saw in the books and on jobsites.” He made a few projects, including a stand for a grinding machine, a rice cooker stand, and furniture repairs for co-workers, and employed the skills for self-directed learning he had honed as a child.

“I am an only child, and my parents were not the mentoring type,” Chris said. “My mom is also an only child, and she felt leaving me to figure things out for myself was a good way of doing things. It was ingrained in me early to self-teach” – including, when he was in upper elementary school, in terms of tackling much of the interior woodwork for a 44-foot fiberglass sailboat his father had built in their backyard. “For some reason, my father let me have at it,” Chris said, and the young boy ended up building chart tables, interior doorways, etc.

By the time the adult Chris visited the Osaka temple, he said, his experiences with the swordsmith had given him enough of a window into the Japanese apprenticeship system. “The Japanese apprentice is not told how to do anything; usually, in the first year, you’re not even allowed to use a tool,” Chris said. “You do menial tasks around the shop, imbibing how people do things. You’re not shown how to use a tool, but they certainly let you know when you do something wrong.”

Chris said he decided, “I’d rather make my own mistakes, and experience things in an order that made sense to me.”

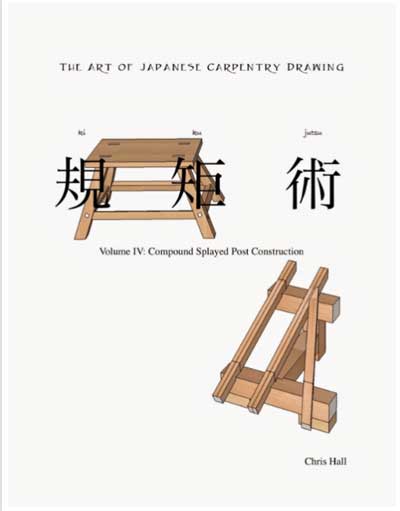

He’s continuing to try to make sense of things, both for himself and for others, through online study groups focused on carpentry drawing studies (for example, the study of a splay-legged structure like a sawhorse, Chris said, is a vehicle for studying a roof steeple), and on developing joinery solutions that do not rely on glue. Chris also has several e-books on the topic of Japanese Carpentry Drawing.

Content for the books initially came out of presentations and articles he prepared for the Timber Framers Guild. Shortly after Chris returned to North America from Japan, he took a Timber Framers Guild course where the second week focused on compound joinery for roof work.

“I found it confusing, and when I got back from the course, I decided I wanted to make a roof model to cement my understanding,” he said. He had a lot of Western books “old books, like how to use a steel square, but I couldn’t make heads or tails of them,” he said. He found the books he had brought back from Japan, along with his ability to read some Japanese “and a smattering of many of the special Japanese characters revolving around wood and carpentry” to make much more sense. So he made a Japanese roof model, and things have evolved from there. As he refined his understanding, and continued making more difficult roof models, Chris said, he wanted to make this information available to others – and he also shares this practical advice.

“If someone’s interested in the sort of carpentry and woodworking I do, my best advice is to jump in and do it,” Chris said. “Don’t be afraid of making mistakes, because they’re your best teachers. When you undertake a learning path, taking the steps forward is what counts.”