Do you set woodworking goals for yourself?

If you are one of those folks who’s always trying to improve your shop skills or challenge yourself with more complex projects, here’s a goal to ponder: Imagine setting out to build the complete history of the steam locomotive in wooden miniature. To perfect scale, without power tools, in your spare time and while raising a family of five children. This was Ernest “Mooney” Warther’s dream, begun at age 28 and completed 64 trains later at age 68.

And as a ripple effect of this remarkable undertaking, a 50,000-square-foot museum, a knife-making tradition and four generations of family woodcarvers have followed from it. You can trace the history of Mooney’s remarkable life and see those functioning steamer engines up close at the Warther Museum and knife factory in Dover, Ohio.

Recently, Mark Warther, the museum’s president, provided me a chronological “sketch” of his granddad’s astonishing life and accomplishments. And at best, I’ll only be able to touch on the highlights of Mooney’s carving history here. For the full story, you’ll have to put the Warther Museum on your list of woodworking vacation destinations sometime in the future. By all accounts, it will be worth your trip.

Mooney’s decision to carve trains really came about as a natural extension of his boyhood experience, according to Mark. “During the 1890s, many boys dreamed of becoming railroad engineers, and my grandfather was no exception. He grew up around roundhouses, where he could see those great locomotives at work. When the railroad companies would toss out their old repair manuals, he would collect them and study how they were built. By age 18, he knew every nut, bolt and rivet that held them together.”

Mastering locomotive design was a personal ambition, and so were all aspects of Warther’s woodcarving. He only received a second-grade education and no formal training with wood. “Granddad was born in an old log schoolhouse, which was his reasoning for why he felt he never needed more schooling; ‘I was born in one, he would say.'”

Through his formative years and into his early marriage to Frieda Warther, Ernest whittled. He considered it to be an enjoyable way to “make shavings,” while working full-time at the local steel mill and raising children. To supplement the family income, Mooney also drew upon his boyhood experience in a blacksmith shop to begin making knives. Mark says that passion for knife-making rivaled Warther’s interest in woodcarving. Some of his earliest knives were created to improve his whittling or, more specifically, to help him tackle the hardness of ebony and ivory, which he often carved. His skill as a metalsmith enabled him to develop carving blades that could hold an edge longer than other options available at the time. One of Mooney’s carvings knives on display at the museum has 139 interchangeable blades, each with a different cutting profile.

“He may have thought that whittling was nothing more than making shavings, but my grandfather became an extremely gifted whittler. A ‘hobo’ taught Granddad how to take a block of wood and, in ten cuts, turn it into a working set of pliers. Grandad was 10 years old when he whittled his first pliers, and he continued to make them throughout his life. By the time he was in his twenties, he could carve a working pliers in under 10 seconds.”

Those wooden pliers became Ernest’s calling card throughout his life. Mark estimates that Mooney carved 750,000 of them in his lifetime, mostly for children who would visit his shop and, later, the museum. The Warther family continues to carve those wooden pliers for every child that visits the museum. “My father David, who was the original manager of the museum and knife factory, carved about 20,000 per year. I carve around 20 to 30 sets of pliers each day,” Mark says. “We feel it’s one of the secrets of our success reaching out to children. Granddad simply loved kids, and both he and my dad would drop whatever they were doing in the shop to help a kid learn how to put something together out of wood.”

At age 28, Mooney created what he considered to be his “Grand Finale” of whittling: a “Pliers Tree” made up of 511 interconnected pliers from a single block of walnut. ” Mooney would spend one hour per day, for 64 days, placing a total of 31,000 cuts into that block of wood. He never removed a single shaving from it, and there are no pins or glue holding it together. It is an example of perfect geometrical progression, and it has been featured in McGraw-Hill calculus books as an example of this principle.”

The sculpture folds open to take the shape of a tree. In its history, it has only been retracted into the closed position once, for Robert Ripley at the 1931 World’s Fair in Chicago. Mark says the Pliers Tree is one of the museum’s visitor highlights.

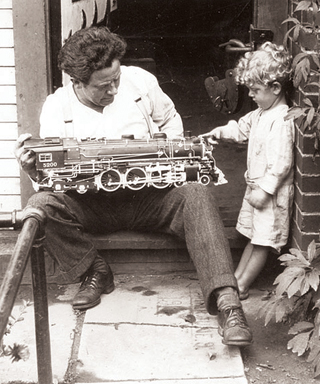

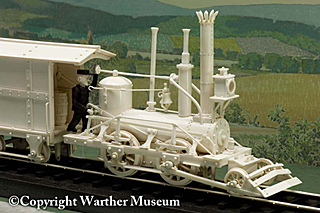

In 1913, Warther announced that he finally considered himself to be a carver, with the clarification that “carving” was whittling with a purpose. He set out to chart the history of the steam locomotive, which he considered to be one of the greatest advancements to civilization. Mooney chose to scale all of his models to 1/2 inch equals 1 ft., and he would carve them from walnut, ebony and ivory. Mark says that his grandfather was still working full-time at the steel mill by day, and his carving time would start at 2 or 3 a.m. and continue until breakfast. Five hour’s sleep was about all he needed, plus a “catnap” after lunch in later years. After a day at the mill and on weekends, it was family time. “My grandparents chose a simple family life, hiking and picnicking with their kids whenever possible. They collected arrowheads (some 5,000 are on display) in the fields around their home, and Grandma collected buttons (around 73,000) for her hobby. Mooney was always a family man first.”

But, Warther was dead serious about his steam locomotive pursuits in the wee hours of the morning. Ten years into his goal, with 15 completed engines and counting, the New York Central Railroad happened to discover him and came calling. They studied the models closely and, satisfied with their complexity and accuracy, offered to put them on display on a train that traveled the country. It was Mooney’s first national exposure as a carver. Following that, the railroad paid Mooney to move to New York City, where his trains were on display at Grand Central Station, and he was on-site to share them.

The Warthers returned to Ohio after three years, feeling that “God never intended people to live in New York City for more than a week,” Mark says. But, knowing that the train-carving hobby wouldn’t pay for itself, Mooney joined forces with his brother Fred in 1927, bought a truck and started a traveling train museum of their own. Frank drove the truck from state to state for 30 years and charged 10 cents admission to view the ever-expanding locomotive collection. It funded Mooney’s hobby as well as Frank’s income right through the Depression and up until ground was broken for the permanent museum in Dover in 1957.

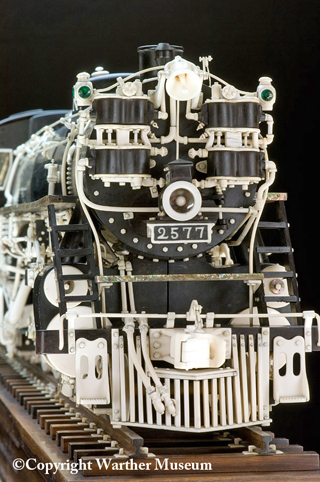

The intricacy and complexity of Mooney’s trains increased through the years, and their timeline stretches from the earliest history of steam-powered engines in 250 BC to the final Union Pacific Steamer he completed on his 68th birthday. Warner never carved a diesel locomotive, because he felt the early models with snub noses “looked like tomato worms.” The carvings range in size up to 8 ft., with parts numbering from several hundred to more than 11,000. Mark considers Mooney’s 8,000-piece 1930 Great Northern Steamer, which includes a 16-in. bell rope and 11-piece ivory hoses, to be the pinnacle of Mooney’s work. The 64 engines were all formed primarily with hand tools carving and draw knives, files, hand saws and eggbeater drills. “Grandad only owned one power tool, a drill press, when he began to carve strictly from ivory at age 72. He felt he needed that when the ivory got too tough for him to drill by hand.”

All of the models feature working pistons, flyrods and wheels, powered from underneath with a small electric motor and a sewing machine belt. There are many other non-motorized moving parts as well. Mooney avoided using glue to secure the pieces; tiny pins were a more durable solution to the glues of the time, and he intended these connections to last a lifetime. He also solved the problem of lubricating the moving pieces by building the bearing surfaces from a naturally oil-impregnated hardwood supplied by the Arguto Oil-less Bearing Company. The oldest locomotive on display has never been lubricated in 97 years, and it continues to function each day on display.

Throughout the train period of his life, knife-making continued to be an important interest for Warther. In 1926 it became his full-time occupation. Mark’s father, David Sr., joined the family’s cutlery business after returning from World War II. The Warther Knife Company incorporated in 1963. Today the company, which is located in the same building as the museum, makes about 50,000 kitchen knives each year in 17 different styles. “We’re actually the last knife-making company in the United States to hand-grind our knives. It continues to be a family-run business. We now have fourth-generation Warthers making knives, and three others from our family help to run the museum. The conclusion of our museum tour is a trip to the knife factory where visitors can see our knives being made daily,” Mark says.

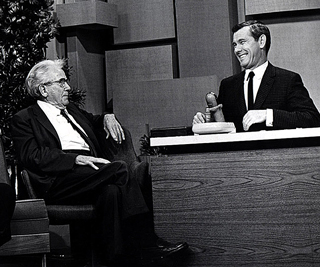

Mooney’s acclaim as a carver grew, and he made several appearances on both the “The Mike Douglas Show” and “The Tonight Show” in the late 1950s through the mid-60s. His last guest appearance was in 1965, after completing the Lincoln Funeral Train when when he was 80 years old. Through the years, Warner also carved walking canes and other gifts for various dignitaries and presidents including Roosevelt, Eisenhower and Nixon. Even so, Mark says that Ernest never considered what he did to be particularly special. It just came naturally to him, and he pursued it until his death at age 82.

“Despite his humility, I consider my Granddad to be a master woodworker and one of America’s unknown geniuses. We continue his legacy here at the museum and knife factory, but all of us put together can’t do what he did in one lifetime. He and Frieda lived 20 lifetimes in one.”