At some point in our woodworking hobby, most of us develop a love/hate relationship with dowel joinery, and it probably leans more to the latter emotion than the former. Dowel joints seem so simple at first, don’t they? Just drill a few holes between the parts, slip some dowels in and push the joint closed. What could be easier? But then, unless you are extremely accurate or downright lucky, a problem rears its ugly head: if those dowel holes aren’t nearly perfectly aligned across the joint, the parts will bind, misalign or not go together at all. The allure of simplicity can be lost quickly to the frustration of drilling accurately.

It befuddled even Jim Lindsay, a marine engineer and lifelong woodworker, more than 20 years ago. His early woodworking joinery training in Scotland had focused on mortise-and-tenons which, though he liked them, were still “laborious and time-consuming” to make.

“Over the years I began experimenting with other joinery systems and, with the exception of the dowel system, I wasn’t impressed with any of the other methods, Lindsay recalls. “The problem was, as most people are aware, that dowels are virtually impossible to align with any degree of accuracy.”

But Lindsay, who once served as the engineering officer on both the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth oceanliners, knew from experience that mechanical problems on the high seas tend to be more difficult than those on dry land. Solving them mid-voyage can require inventiveness. He decided to approach the challenge of dowel joints with the same seaman’s sink-or-swim tenacity.

And so, in 1995 he began drafting and prototyping a doweling device that would cover most woodworking applications. Sure, there were other doweling jig solutions already on the market, but Lindsay found them to be either poorly designed or cheaply made of plastic. There was one exception: a popular self-centering design that’s still in use today. While it’s functional and accurate, the jig has limited versatility.

After a couple of weeks of noodling over a new approach to doweling, however, Lindsay recalls feeling a bit lost at sea.

“I came to the conclusion that the concept was impossible. But then I reminded myself that nothing is impossible, and I decided to continue,” he says. “A month or so later the idea suddenly surfaced, and I had it solved. The strange thing was, although the problem (of designing a better doweling jig) was extremely complicated, the answer was simplicity itself.”

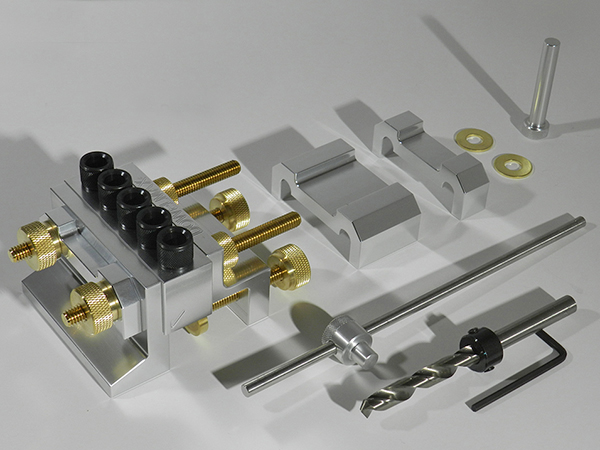

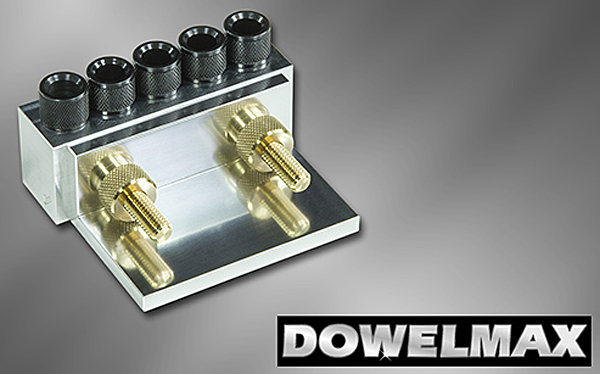

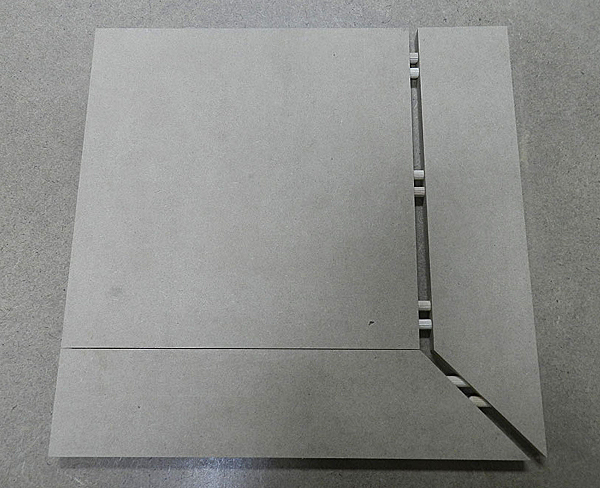

His breakthrough was the jig he calls Dowelmax. Made of aluminum and brass, it clamps onto a workpiece, and five interchangeable hardened-steel guide bushings provide for accurate drilling. What distinguishes this jig from some other doweling jigs, however, is that Lindsay’s design can be disassembled and reconfigured in a number of ways to suit a variety of joint applications.

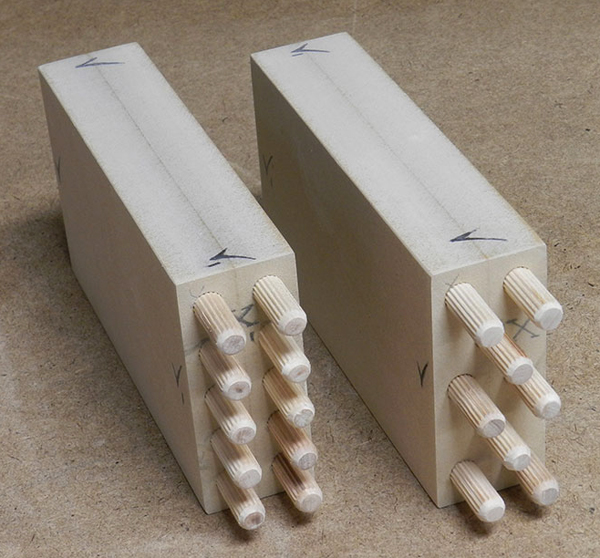

“To be completely honest, Dowelmax is capable of performing virtually any dowel joint imaginable: edge to edge, end to edge, edge to end or face, and both picture frame or drawer-box style miter joints,” he says.

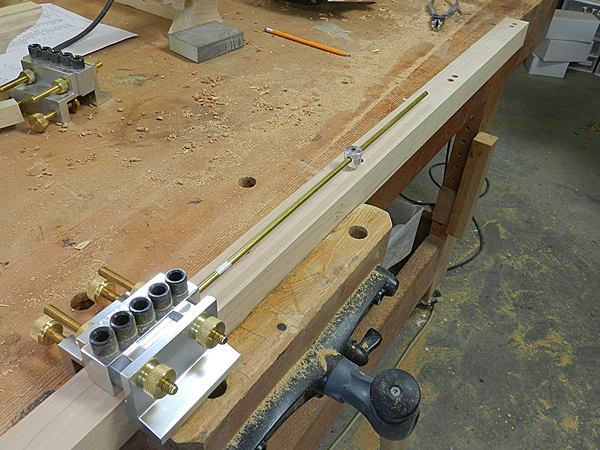

Included spacers can be used to center the dowel holes over a range of wood thicknesses, as well as to create offset joints. A rod-type distance gauge steps the jig off accurately when it’s used on long boards, and an indexing pin can locate the jig to repeat its drilling pattern across wide workpieces. Dowelmax also can be set up to drill double or triple rows of dowel holes for making joints on thicker stock.

“All applications are within thousandths of an inch, and most joints can be completed in less than five minutes,” Lindsay adds. “The system is accurate, versatile, reliable and fast, and it’s intended for both beginners and professionals.”

If the promise of making dowel joints more easily sounds enticing, here’s another reason to give Dowelmax a go: dowel joints are exceedingly strong. Years ago, Lindsay set out to test a German experiment that concluded that dowel joints are actually the strongest joint option available to us. He designed a hydraulic press and tested Dowelmax joints against traditional mortise-and-tenons, plus several other common joint styles. You can watch those strength tests in a series of videos Lindsay made by clicking here.

And the verdict?

“You can imagine our surprise and elation, after all the tests were complete, that the dowel joint was approximately 30 percent stronger than a comparable mortise-and-tenon joint!” Lindsay says. “These same tests have been repeated many times over during the ensuing years with the same result.”

He’s concluded, through further study, that there are three reasons why Dowelmax joints are stronger than mortise-and tenon joints: the accuracy with which they can be made by the jig, their geometric configuration and close spacing.

Here’s another interesting fact from Lindsay: a dowel joint’s strength doesn’t necessarily increase by adding more dowels to it. “Double and triple rows (of dowels) in our experience are usually unnecessary,” he says. “To illustrate this point, a single-row dowel placement is actually stronger than the wood itself.”

Lindsay’s hydraulic-press testing also revealed that Dowelmax joints exceed the strength of ordinary wood biscuits, pocket screws and even Festool Domino joints.

While the process of bringing Dowelmax to market 20 years ago has had some challenges, particularly in terms of patenting, Lindsay says he wouldn’t change it and he’d do it all over again if he had to.

He feels the patenting system in Canada, where he lives, and in the U.S. is “antiquated, overly complicated and has a multitude of flaws.” For aspiring inventors, he warns to be careful who you share your ideas with, and don’t believe that a patent protects your idea completely.

“At the most, it’s a deterrent. Patent laws are so convoluted it would appear to be easier to infringe a patent rather than protect one,” he adds. “Our patent has been infringed at least twice to date: by a Chinese company, which I did anticipate, and a North American company, which I naively didn’t anticipate.”

Still, the gratification of making a jig that truly works better has outweighed the grief for this engineer and inventor.

“The people who have (Dowelmax) love it, and we constantly receive emails of appreciation,” Lindsay says. “This is not a scientific breakthrough, but it is important to woodworkers, and it will be my legacy. I also predict it will be the future of woodworking.”

Learn more about Dowelmax, its accessories and other products Lindsay and his team at O.M.S. Tool Company have invented by clicking here.